To my other TR6 pages.

March 28, 2015

Dashboard

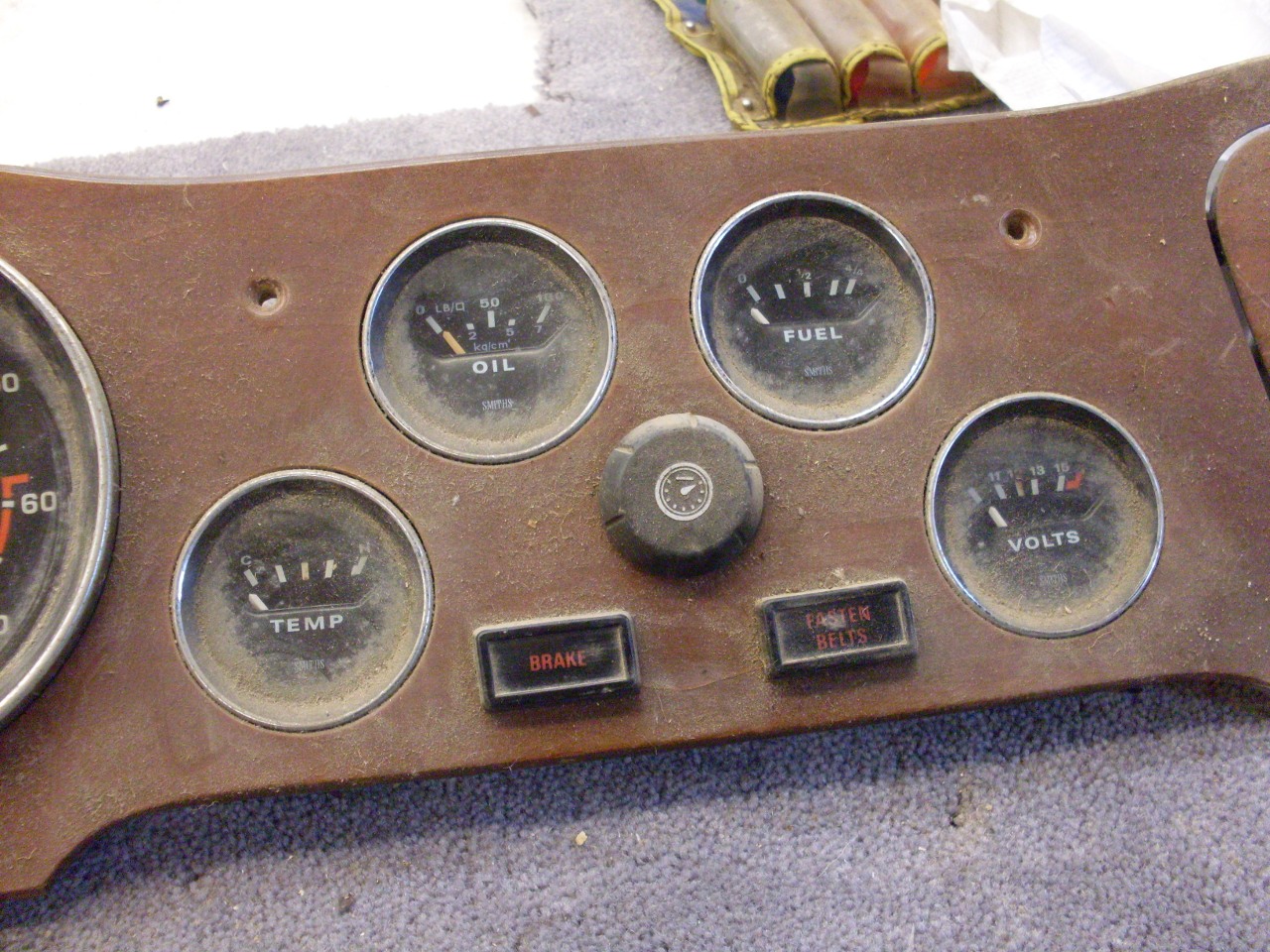

One

of the coolest things about the TR6 and some of the other British cars

of the era was their fully instrumented wood grain dashboards.

Never mind the marginal practicality of this in a roadster with

the top down most of the time, it was an important style statement that

became part of the mystique of the marque. The TR6 outer dash is

a plywood base veneered with what appears to me to be walnut or

something close to it.

My dash, other than being grimy,

was in pretty sound condition, althought the finish was not. It

was cracked and crazed from four decades of temperature and humidity

extremes, not to mention frequent strong doses of UV radiation and the

occasional dowsing from an unexpected shower.

On

close inspection of the dash from all sides, I determined that I could

easily save the dash, but the finish had to go. This is where I

began to consider the range of options for either rebuilding or

replacing the dash.. Many have commented on the difficulty of

removing the factory finish, and I wasn't sure I could remove it

without doing some unintended violence to the thin veneer. In

pressing on, I too was struck by the tenacity of the finish.

Wimpy strippers don't faze it. A good strong methylene

chloride stripper will remove it, but it's a slow, iterative process.

In

the scraping required by the stripping process, I did indeed damage the

original veneer in a few places. It's very thin, and is very

vulnerable in places where there is short grain between two edges.

Considering

the damage, I deemed the dash unusable in that condition.

This started me running through the options. There are

aftermarket replacement dashes in many different veneers. Some of

the ones I've seen are beautiful, but expensive, and since my dash was physically

sound, I didn't even consider buying a new one. All I needed was

to restore mine cosmetically. All I needed was new veneer.

Once

I got on the path to new veneer, I realized how wide the range of

possibilities was. Broadly speaking, a veneer surface doesn't

have to be wood, but to my mind, using some non-wood finish would violate the spirit of the car. Even limited to wood, the

possibilities are many. There are hundreds of types of wood

veneer, domestic, exotic, and specialty. I gave it a lot of

thought.

Now I've been a hobby woodworker for decades, so I have

at least a passing familiarity with quite a few kinds of wood.

When thinking of a dashboard wood, the first thing that will come

to mind for many people is walnut burl. It's almost a cliché for

very upscale cars, and is widely cheaply imitated in lower class

wanna-be cars. I find walnut burl very beautiful, but a little

too obvious, a little too pretentious, and also a little overdone.

I considered quite

a few kinds of wood, mostly exotics. I've worked with padouk and

purpleheart. They are gorgeous when freshly finished with

strikingly rich colors. The colors don't last well, though,

tending eventually toward brown. I considered several kinds of

mahoganies and rosewoods. Some of the rosewoods had such bold

grain that it seemed too overpowering.

While I struggled with

the veneer decision, I prepared the dash for whatever I finally decided

on. Mainly, this involved sanding the surface smooth and flat,

and repairing the few voids in the old veneer. I also filled in

the five countersunk dash mounting holes. The countersinks looked

to be kind of hogged out, so I'll redrill and countersink after the

final finish is on.

Also filled some voids and fixed a few stripped holes on the backside.

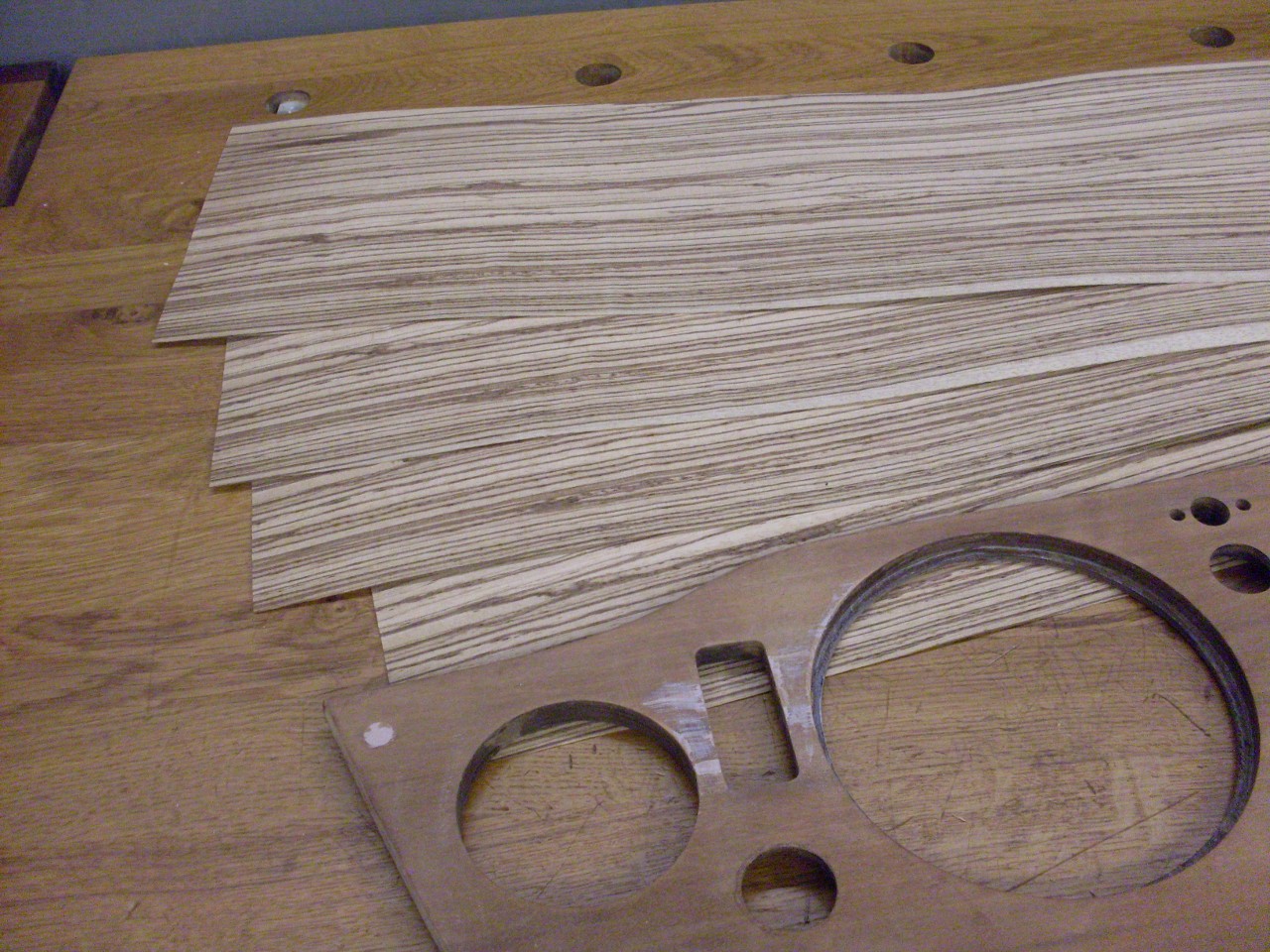

Enough

stalling. It was time for a decision. In the end, I came

back to one of my all time favorite woods--zebrano, or zebrawood.

When zebrawood is quartersawn (cut on a line that goes nearly

through the center of the tree), it has a striking grain consisting of

more or less straight lines of alternating tan and dark brown.

The dark brown is close to the color I plan for the interior.

I'm not totally sure how it will look in the car, so it's a bit

of a leap of faith.

Raw veneer is commonly sold by the lot.

A lot consists of a number of consecutive sheets of veneer,

meaning that they would have been adjacent to each other in the tree.

Sheets in a lot will not only have consistent color, but the

grain pattern of adjacent sheets will be nearly identical, with only

subtle differences. I went on a website that posted photos of the

lots they had in stock, so I could pick the one with the grain pattern

I liked. The lot I bought had four sheets, but any one of them

was big enough to do the dash.

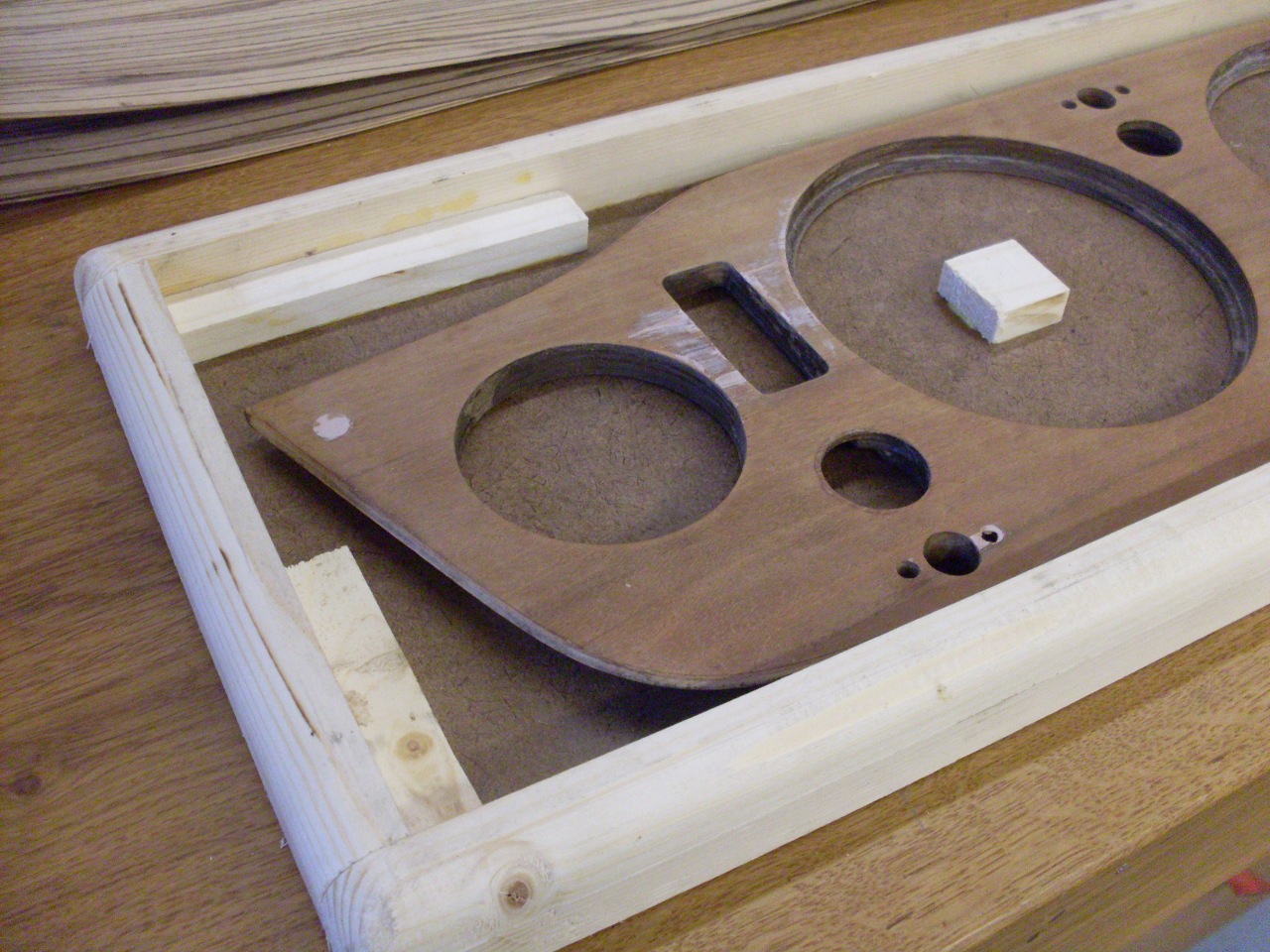

While

there are a number of methods to attach raw veneer to a wood substrate,

most of the better ones involve some serious clamping. Just

stacking weight on top of the veneer is often not practical since the

10-12 pounds per square inch needed for a good bond can add up to

thousands of pounds for something the size of a dashboard.

Luckily, there is an easy way to provide this pressure that

doesn't involve lifting heavy weights. A vacuum press uses normal

barometric air pressure to apply clamping force. It does this by

evacuating the air out of a sealed bag that contains the items to be

clamped. With little air pressure inside the bag, normal room air

pressure provides the clamping pressure.

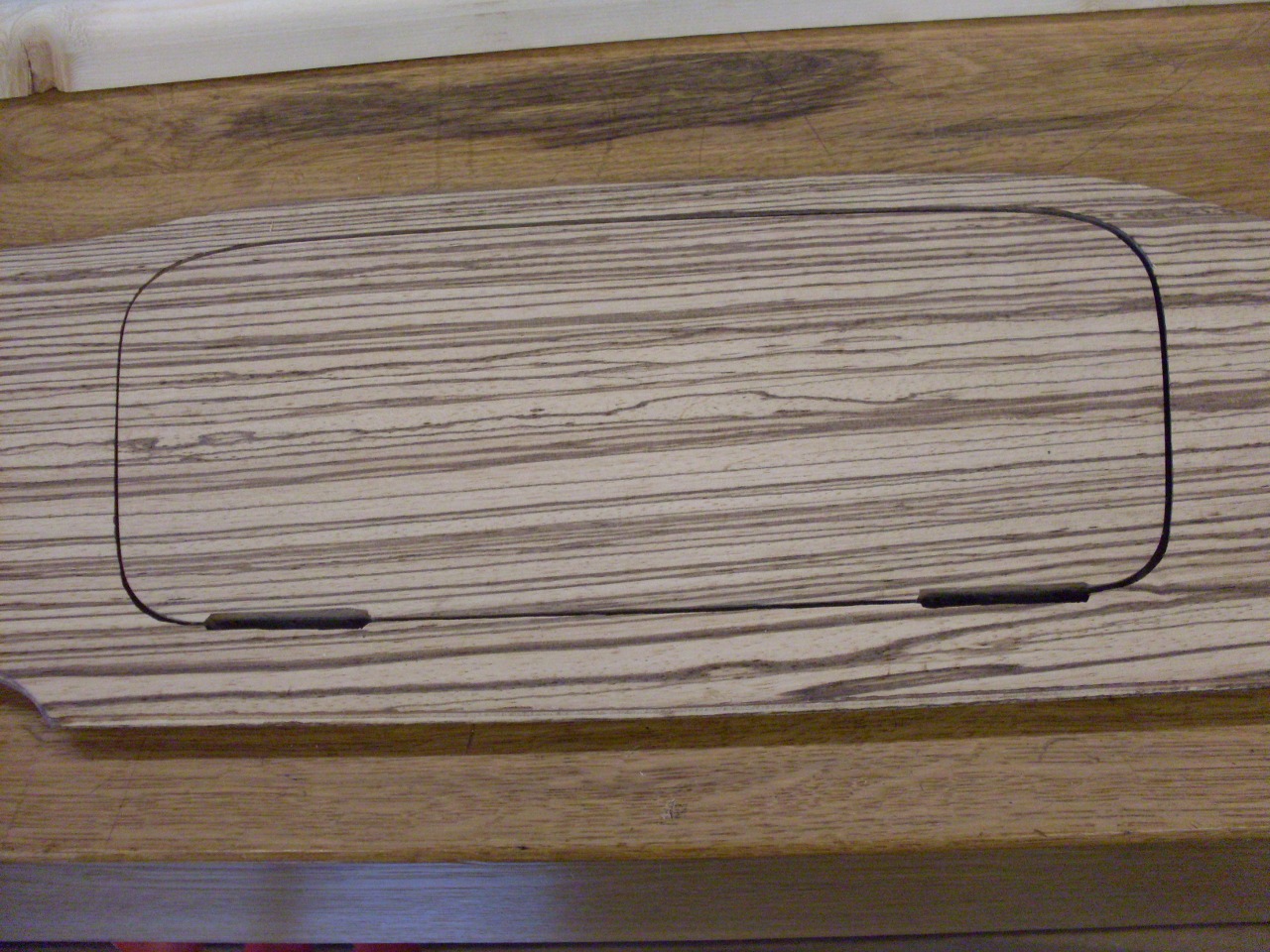

I fabricatred a bag out

of heavy vinyl sheet (like what our rear windows are made from) that

was big enough for the dash. I did build a vacuum pump, but only

because I can use it for other things. A much simpler pump would

have worked as well. People have even used shop vacs.

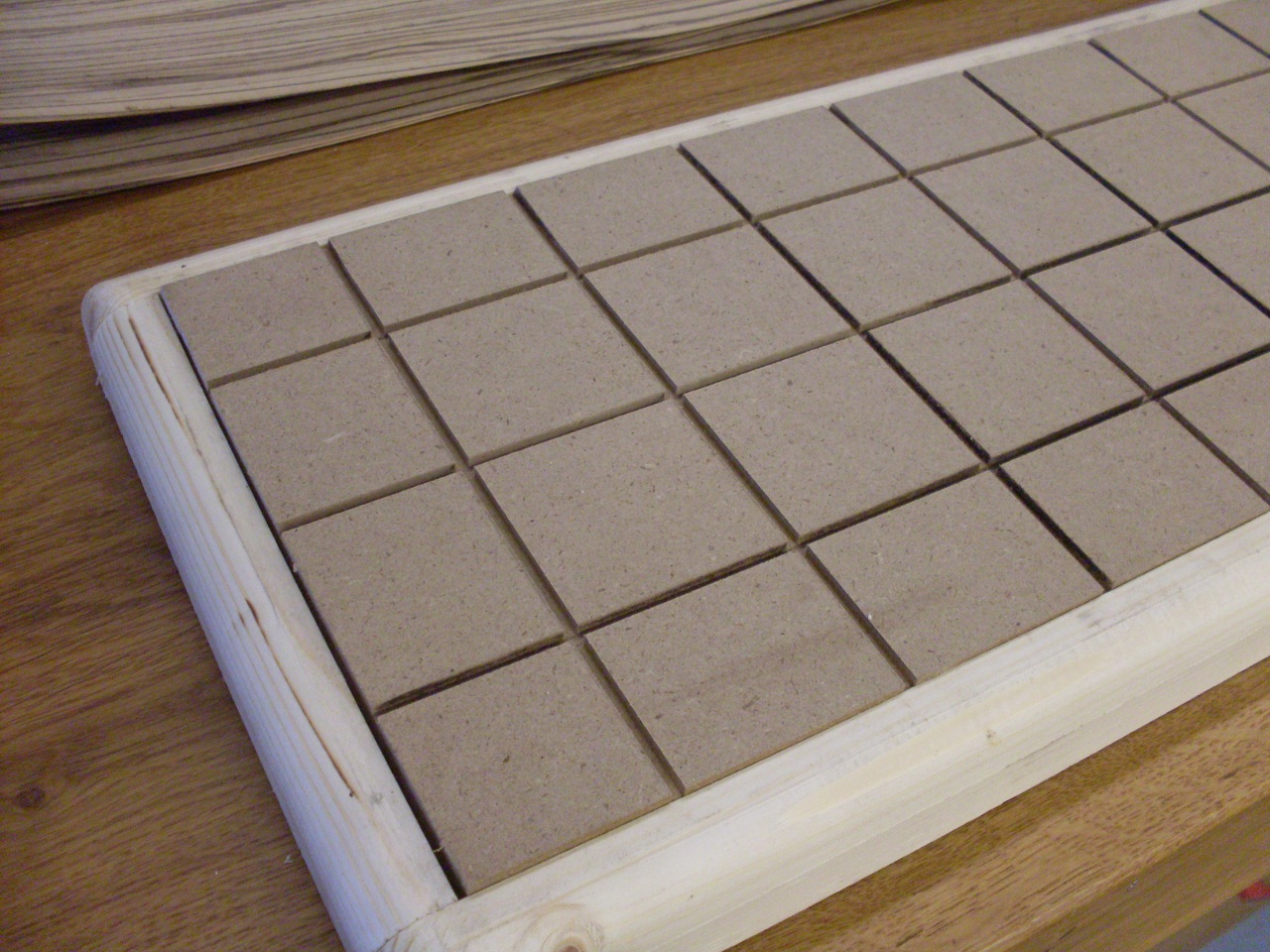

I

built a shallow frame to hold the dash

and veneer. On top of the veneer goes a flat panel that applies

the pressure to the veneer. The panel has grooves cut in it so no

air can get trapped in cavities in the bag. I decided to veneer

the glove box door at the same time as the rest of the dash, so I taped

it on the backside to keep it registered with the surrounding dash.

This

guarantees that the grain will be continuous across the door, but would make

cutting the door out a little more tedious and risky.

Then in the bag under vacuum for an hour or so.

Another

couple of hours to finish curing, and I started trimming. A very

sharp Exacto knife worked pretty well, which of course meant that one

of the biggest risks became blood stains on the veneer.

After

sanding the edges flush. The glove box door seemed to fit nicely.

All the exposed edges of the dash will be painted brown

eventually.

The

glovebox door gets veneered on its backside, too. The factory

appied the veneer vertically on the back, so I did too. I was

able to use a scrap from the dash and cut it in half so the door

backside veneer is bookmatched, or mirrored.

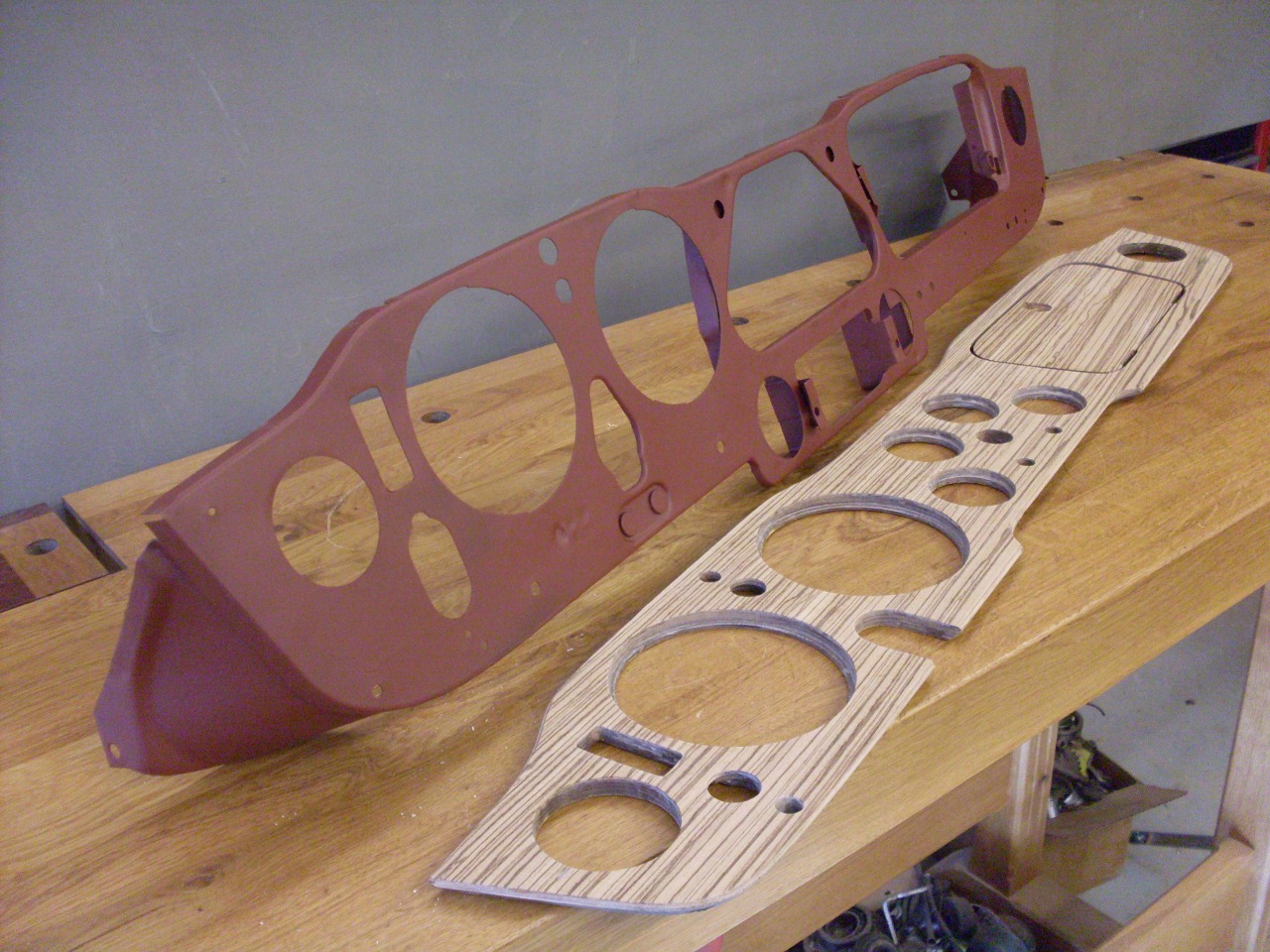

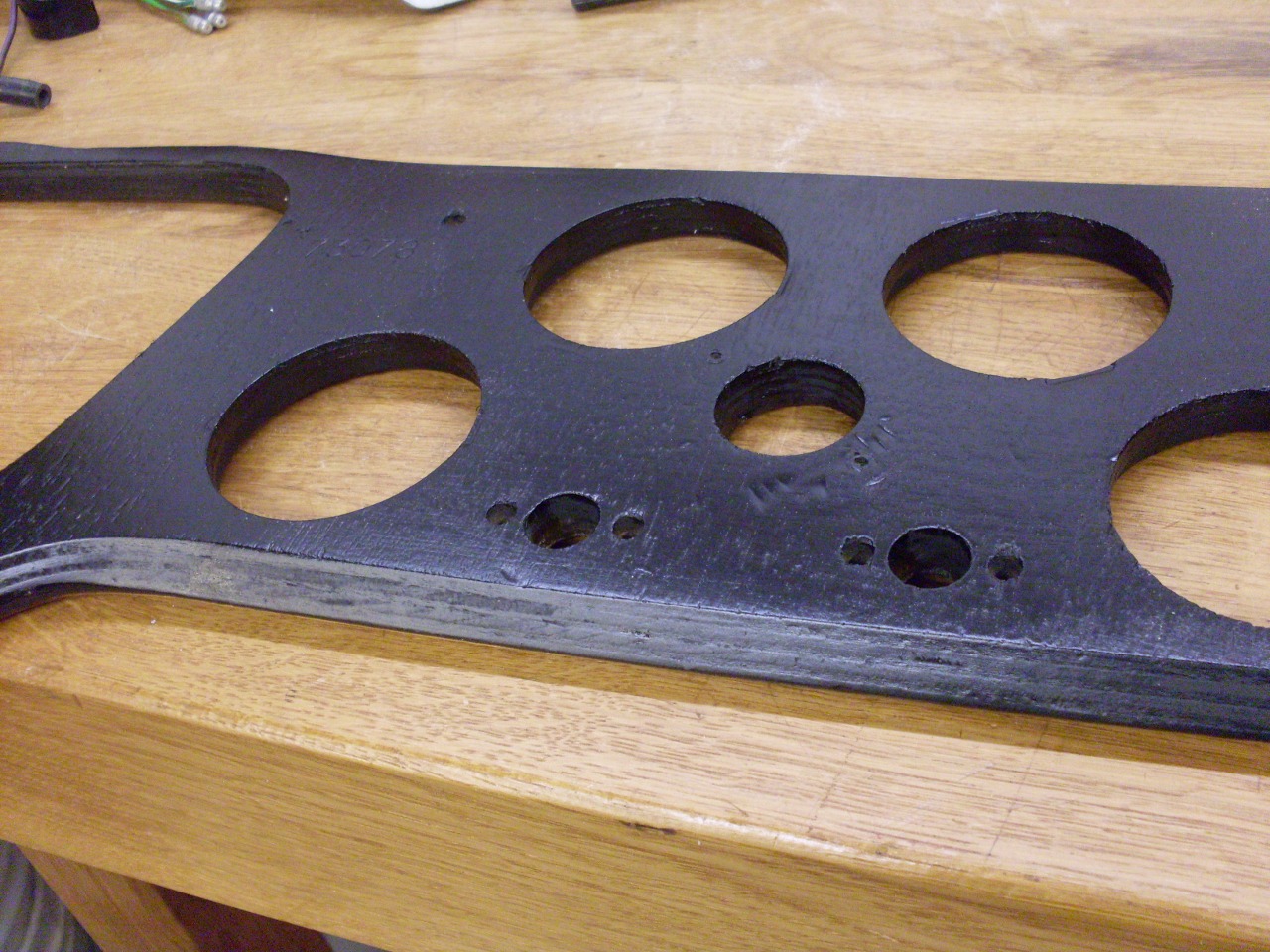

While trying to decide what kind of finish to apply, I cleaned up and primed the metal sub dash.

For

the finish, I obviously wanted something good looking, but also

durable. The environment for the dash is essentially outdoors,

with wide swings in temperature and humidity, and strong doses of

ultraviolet light. I've used many of the products available to

the mass market through big box stores, and most of them worked OK, but

I felt there were probably better products available. I

researched true marine varnishes, and finally chose a European varnish

popular with the higher end boat crowd. It isn't cheap, but I was

able to get a half-liter can which was plenty for the project.

Staying

fairly close to the recommended application schedule on the can, I

applied a few thinned coats, which tended to soak into the wood.

I followed this with unthinned applications for a total of nine

coats, sanding between coats to level any imperfections.

I don't

have a dedicated finishing room, so I expected the usual dust nibs in

the finish. This isn't a big problem since I planned to cut back

the gloss anyway, a process that will remove those kinds of

imperfections.

Here

is the dash after the final coat was dry, but before any final leveling

or adjustment of the sheen. A good varnish finish suitable for

outdoors takes time. After nine

days of one coat per day, the finish is dry to the touch, but is still

soft. It can take another week or more to get the finish hard

enough

to sand. I waited until a finger pressed hard onto the finish

would not

leave an impression. It was about another ten days of leaving it

on a window sill in direct sun.

I

glued the speedo and tach veneer cutouts to a substrate with the idea

of testing finishing techniques on them first, before applying them to

the dash itrself. It gave me a chance to try various rubbing

products and see various sheens before I committed myself to the dash.

I wasn't totally sure what level of gloss I wanted, or even how

to get it. One advantage of using a high gloss varnish is that it

can be rubbed to just about any level of sheen from matte to high

gloss. Even if I wanted a very high gloss, the rubbing steps are

necessary to get rid of the surface imperfections of the raw varnish

film.

The

pic below shows one of the test panels with the right half untouched

after varnishing, and the left after a regimen of fine wet

sandpapers and a series of hand rubbing steps. That was about the

maximum gloss I was interested in, and I knew how to get there. I

could stop short of that level for a little more of a satin look.

Here is a section of the dash part way through the process. I really like this look, but went on for a little more shine.

After a little more work, I had this. I decided to back off on the sheen just a little from here.

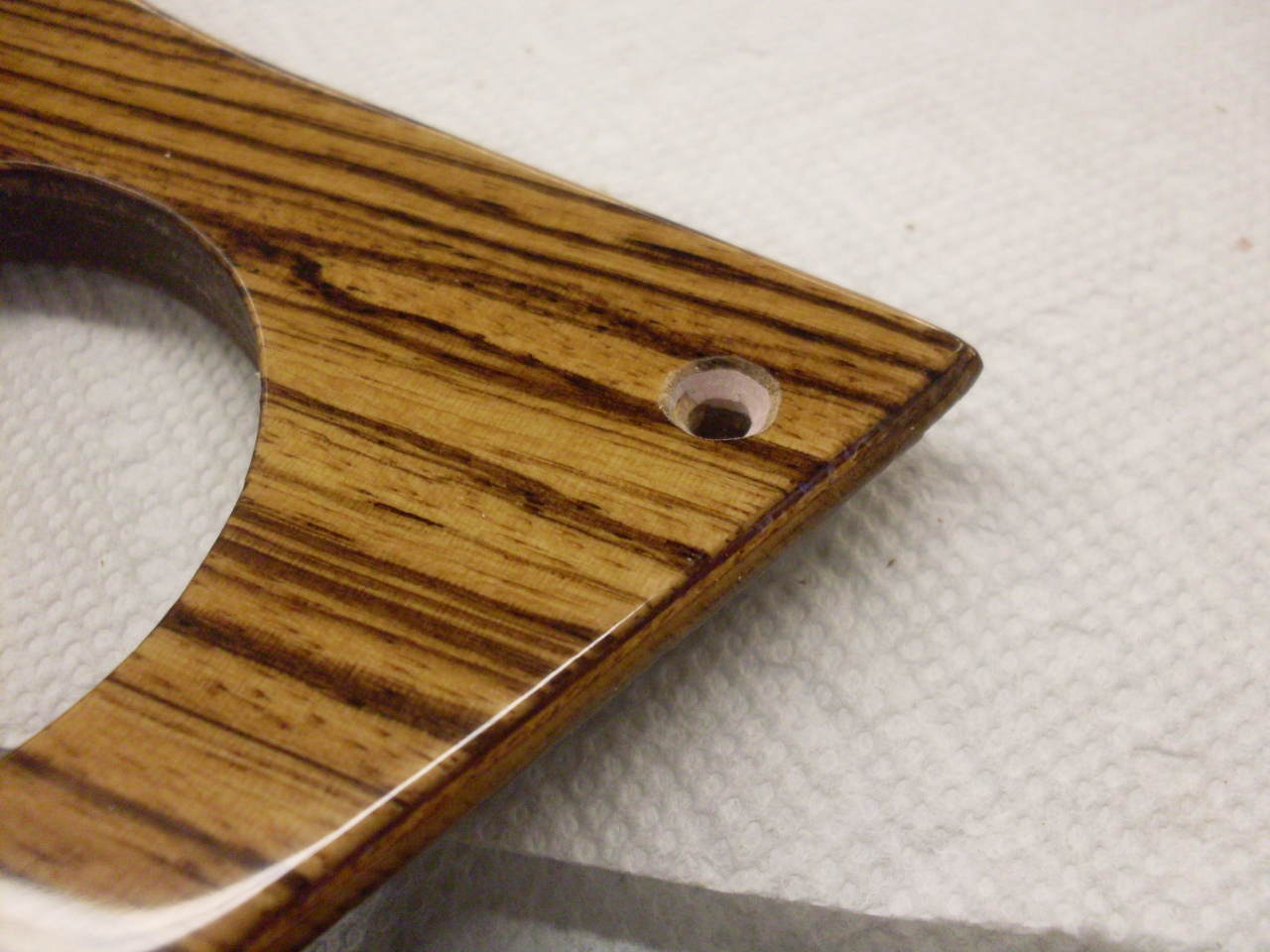

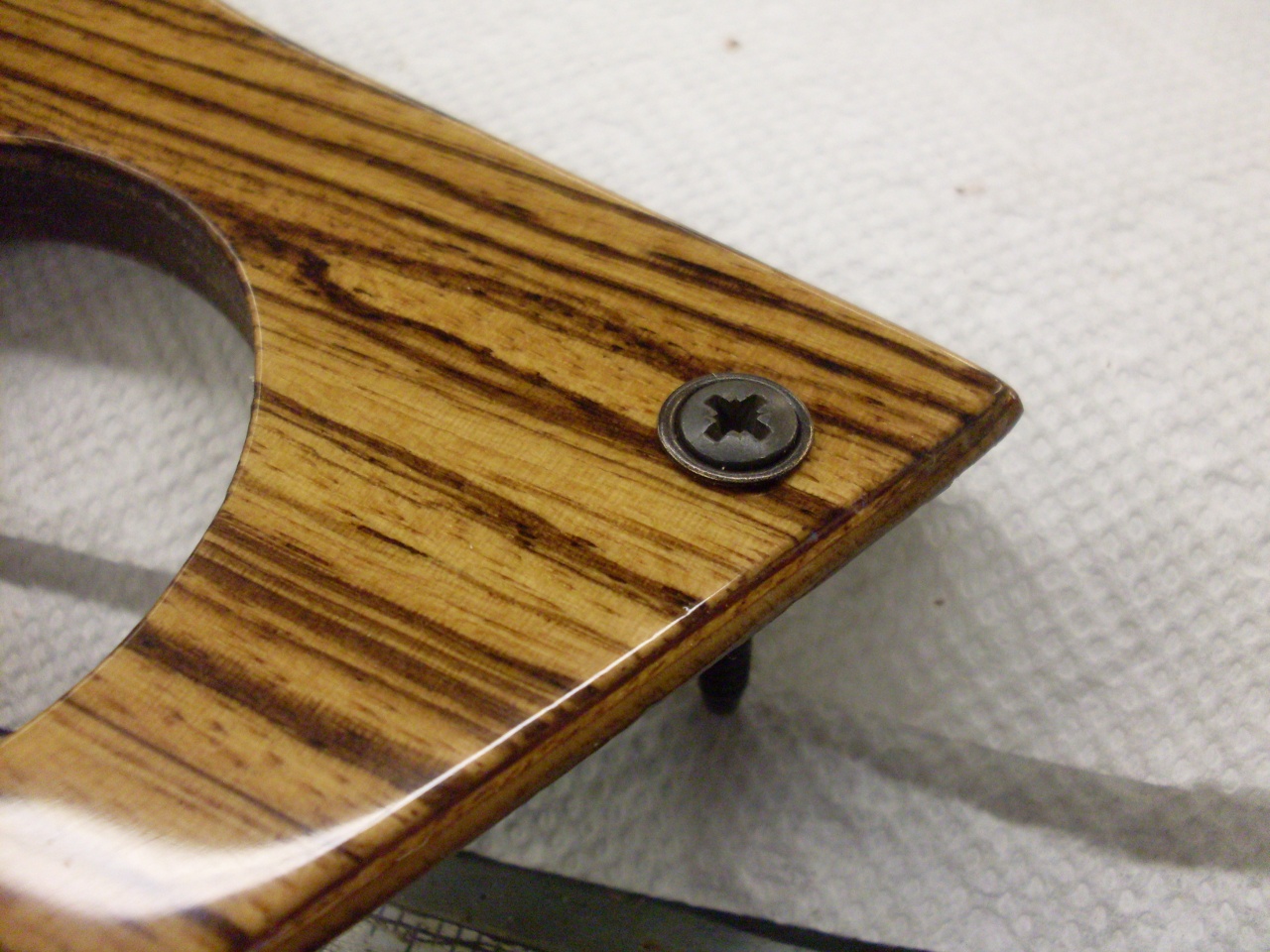

Here are a few more photos of the glove box door raw, at sort of a semi gloss stage, and nearly full gloss.

Here is a view of the parts together. I think I'll leave it at this level.

I then had to redrill and countersink the holes for the dash mounting screws.

Painted the backside and the instrument holes black just for a more finished look.

This puppy is done!

Postscript

The

dash looks nice, but we can't really have a fancy zebrawood dash

without a matching fancy zebrawood gearshift knob, now can we?

I believe this is the original shift knob. I think it's walnut. It lost its emblem decades ago.

I happen to have a chunk of zebrawood. I cut a couple of little pieces off and glued them together.

I

took a hardware store threaded coupler and cut some grooves in the

outside for better grip, and epoxied it into a hole in the center of

the zebrawood block, then sawed off the corners of the block to make it

a little closer to round.

OK, still needs some work.

Put a cutoff bolt mandrel in, and put it in the lathe.

This looks better. The badge is actually a tie tack I bought off the Internet. The stock knob always felt sort of delicate to me. The new one is a little fatter.

I

resisted the urge to pot the whole thing in plastic, as is pretty

common. I didn't even use the same varnish as for the dash.

Instead, I used a simple oil finish, which I think feels better

in the hand.

I

didn't realize until this was almost done that the original knob had a

rubber isolator inside, presumably to transmit less transmission

vibration to the knob. If I had known earlier, I might have tried

to duplicate it. Oh, well, live and learn.

Please send comments to Ed at: elhollin1@yahoo.com

To my other TR6 pages.