To my other

TR6 pages

January 12th, 2015

Gauges

Besides

the speedometer and tachometer, the TR6 of this year had a complement

of four gauges: fuel level, coolant termperature, system

voltage,

and oil pressure. The first three are electrically operated

while

the oil pressure gauge is mechanical. The three electrical gauges are

mechanically identical inside, and only differ in their scales and

labeling.

I'll describe what I did to the voltmeter here, and just say

that

the others were the same.

All the gauges were dirty and crusty, but apparently intact and

undamaged. I had no idea if they worked or not.

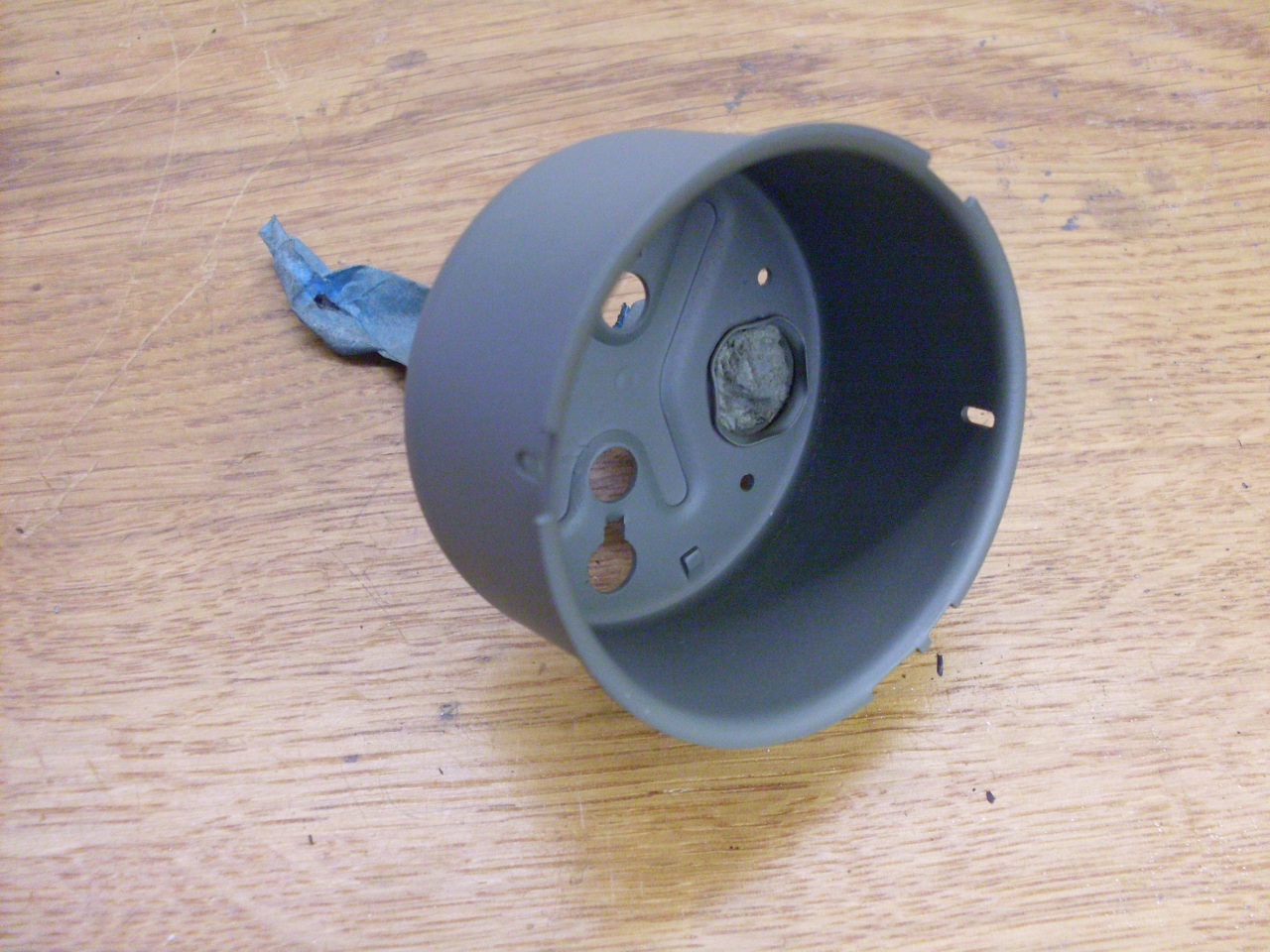

The

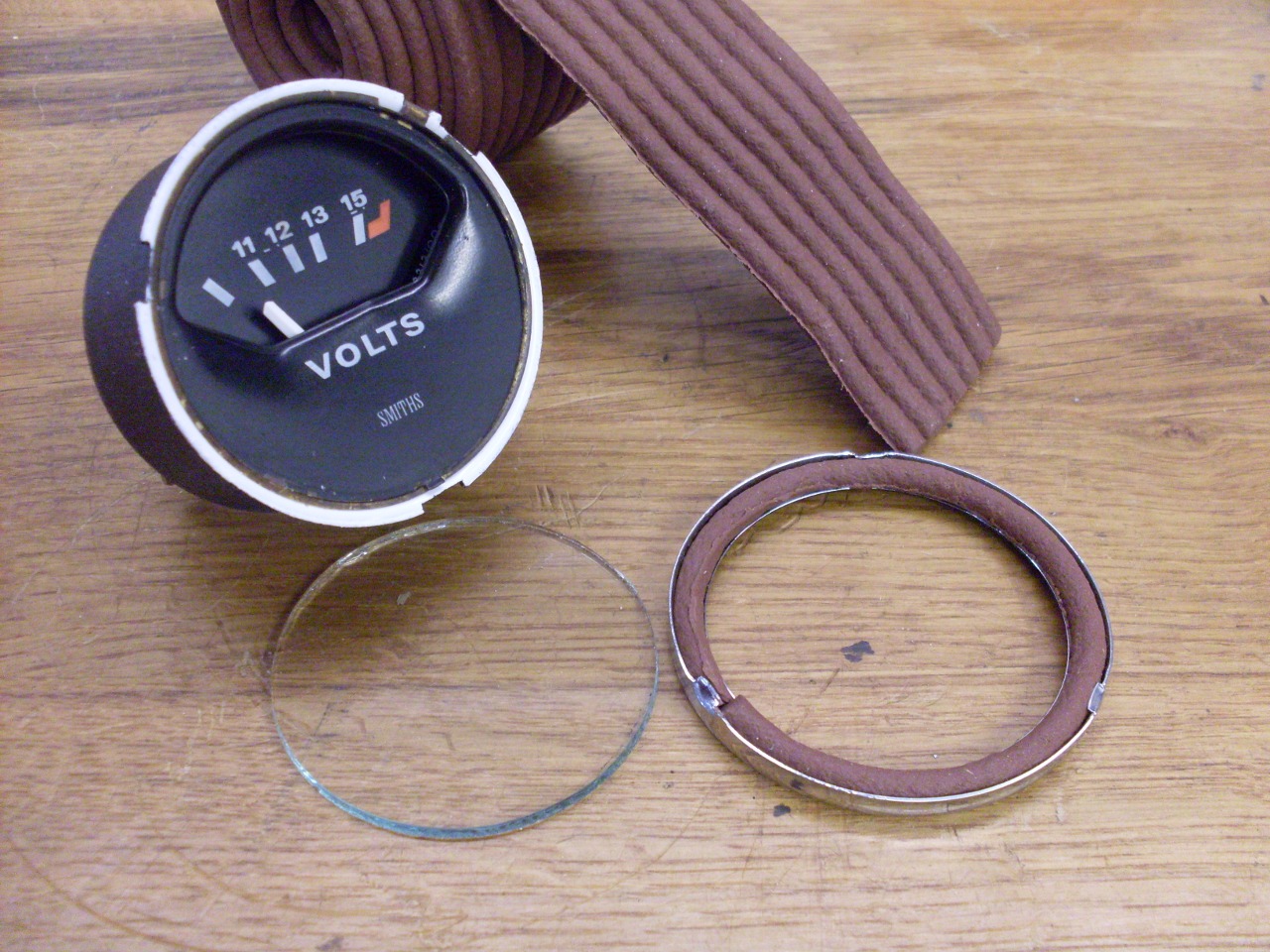

front bezels come off by twisting them, bayonet style, until they

release. Smiths used some kind of sealant between the bezel

and

glass that had long since petrified.

The

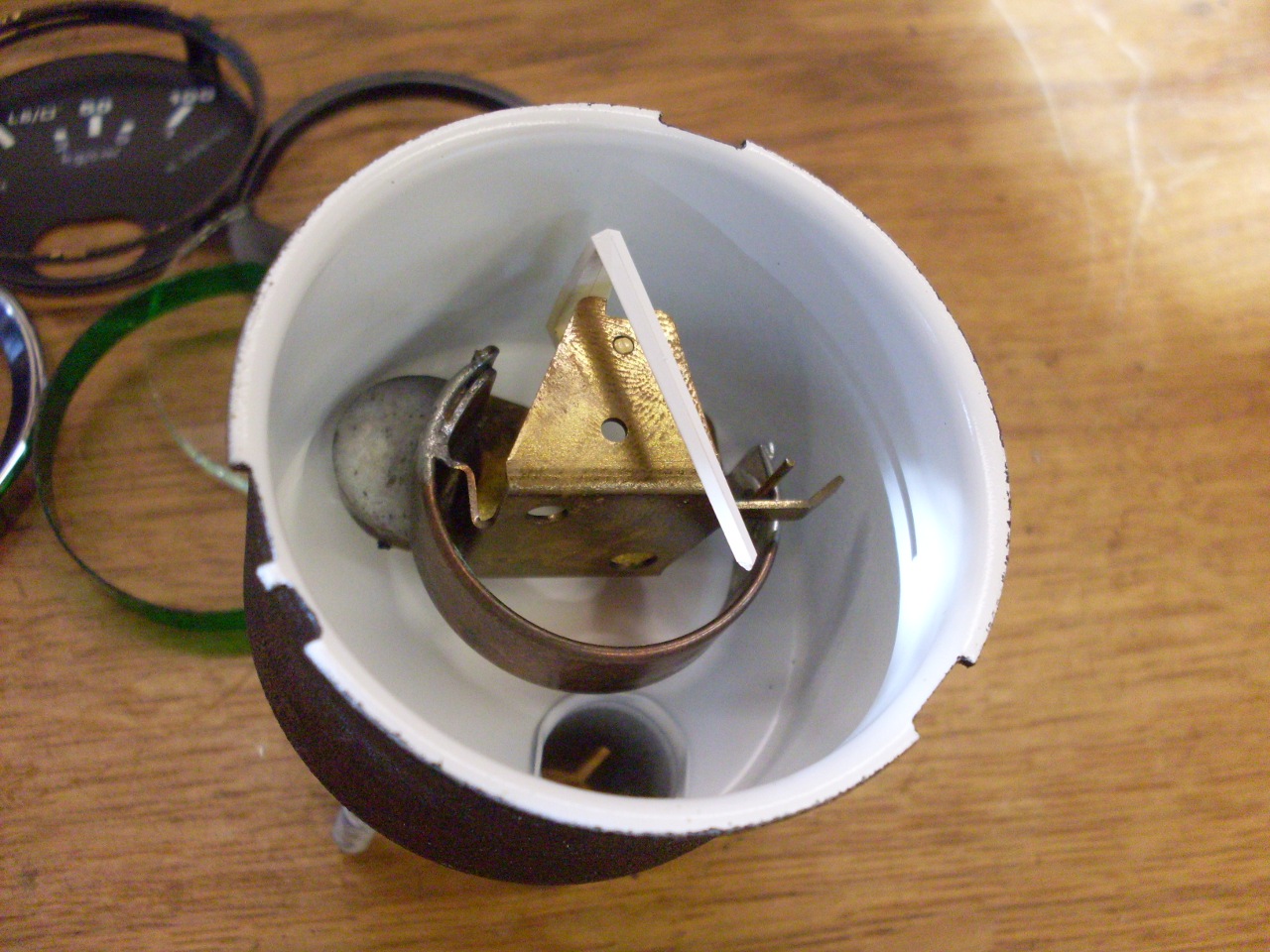

innards are released by removing the two barrel nuts on the back of the

body. This reveals the actual meter movement. It

also

revealed that the colored plastic lens for the gauge illumination bulb

had been fried. This was the case in all of the gauges.

I worked on the cases first. I removed the toasted lenses.

There isn't much hope of finding good replacement for these,

but I wanted to preserve the green illumination for the gauges.

I looked into a few alternatives. One was to use

LED bulbs. These can be had in many of the popular bulb

sizes, and they come in a range of colors. Dimming can be an

issue with LEDs, and even for those that claim to be dimmable, it

typically can't be done with a rheostat based dimmer that the

incandescents use. Even with a proper dimmer suitable for

LEDs, the dimming action is often different than for incandescents,

especially at low levels of illumination.

I also considered making lenses from green colored film. I

had some film, but didn't get very far on this idea.

Another option was to convert the electrical gauges to use the

filtering suystem used on the oil pressure gauge. The oil

gauge uses a strip of green plastic to cover the openings in the side

of the dial. These openings are how the light from the bulb

in the case gets to the dial. I think this would have worked.

The solution I finally landed on was to use little green covers for the

bulbs. These covers are made for this purpose, and I bought

them from a supplier of gauges and gauge accessories.

The cases were blasted, dipped, primed, and painted.

The dials were dirty and had some stubborn smudges on them.

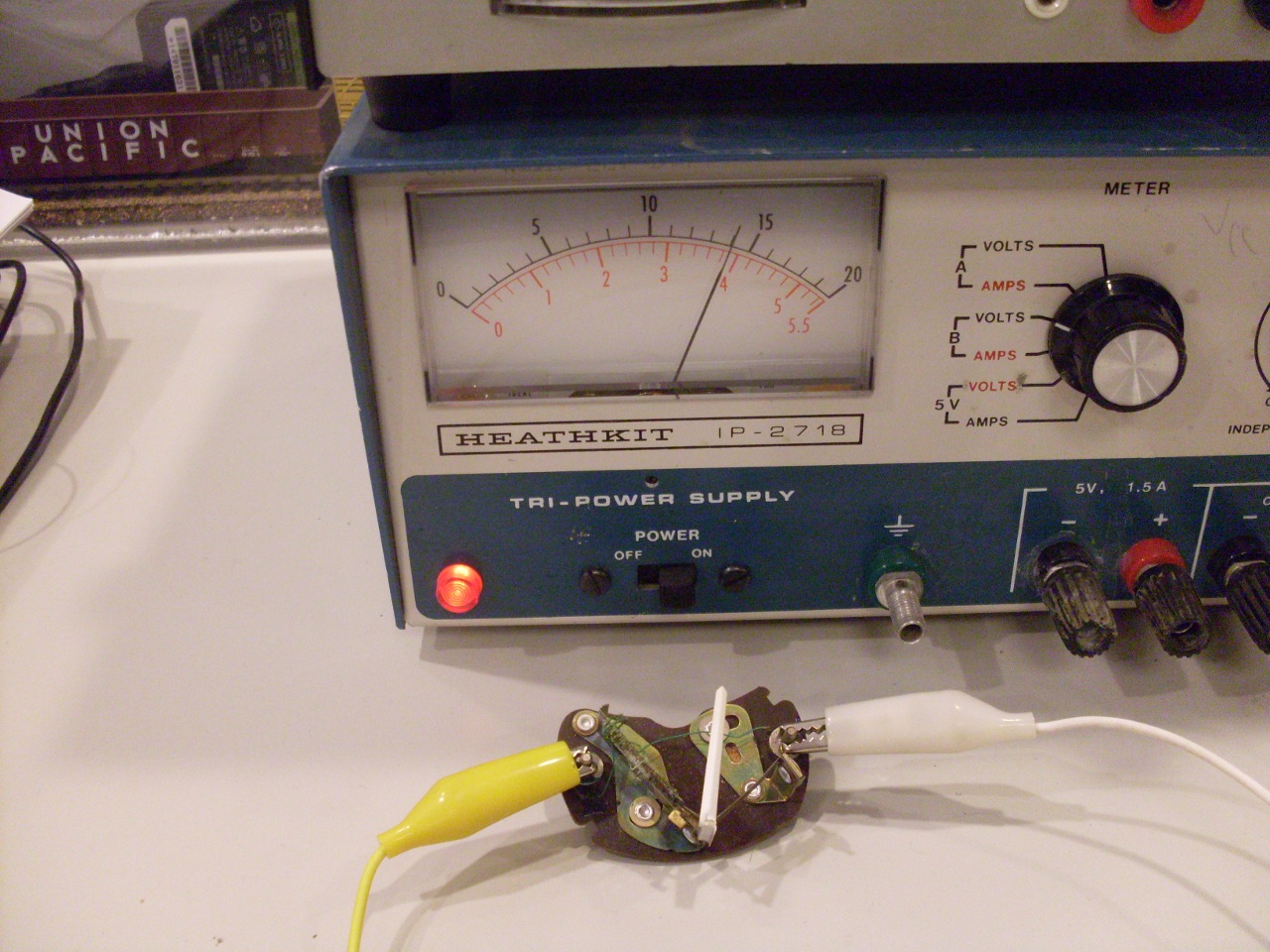

Then I turned to the innards. A quick check to see if the

movement is working.

These

meter movements are not like those found in many test instruments.

These work by sending the current to be measured through a

small

coil of resistance wire, where it heats a bimetal spring,

and spring bends as it gets warmer. This bending is

translated into motion of the pointer. This design is

relatively rugged and cheap, but not all that precise or accurate.

It also implies a scale that is non linear, but the main

feature if this thermal approach is that it is very slow to react.

It can take tens of seconds for the pointer to reach a final

position. This may not be a big deal for the fuel gauge or

even the temp gauge, but consider a situation where an intermittent

short in the electrical system causes a voltage drop large

enough to make the lights dim and the engine miss. The slow

voltmeter will ignore this and continue to show a rock steady normal

reading. This is why many people consider these guages not

much better than idiot lights. The temp gauge doesn't even

have numerical markings on the dial.

Even though the

construction of the movement is the same for all three electrical

instruments, they aren't interchangeable. The

coil for the voltmeter has a higher resistance, since it may be exposed

to voltages well over 14 volts, while the other gauges would normally

operate under 10 volts due to the voltage stabilizer.

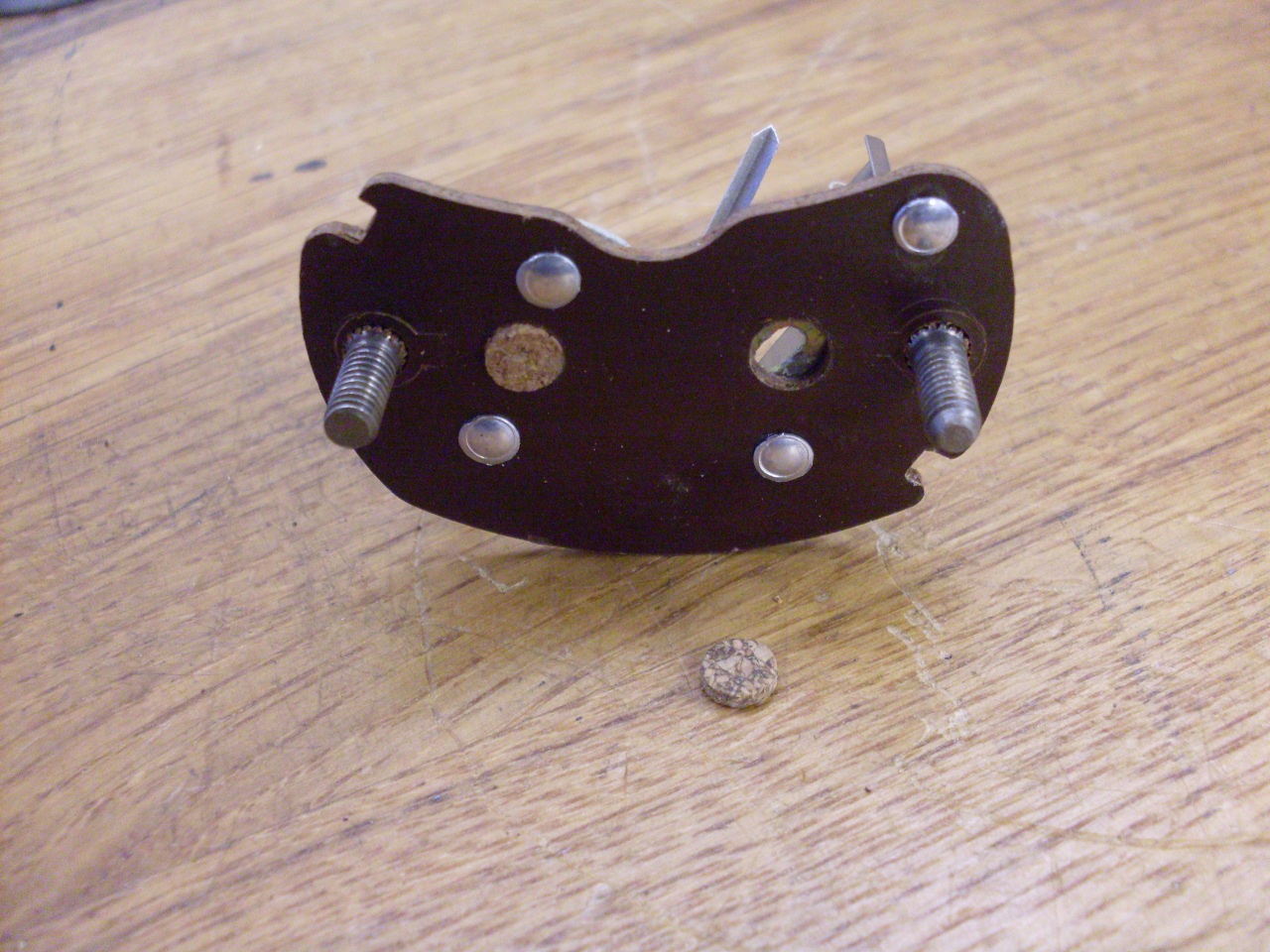

There are a couple of access holes in the rear of the electrical gauges

that offer a way to adjust for proper calibration. I've never

seen any explanation of how to use them, but I fiddled with them a

little to get my voltmeter to be a little more accurate in the center

part of the range. There are supposed to be little cork disks

closing off the access holes, but about half of mine were missing.

A 3/16" hollow punch makes a plug that fits perfectly.

So, with clean cases and working guts, I put everything

back together. I don't know what kind of sealant

Smiths used between the bezel and glass, but I opted to use a stip

caulk compound that worked well. I know there are O

ring seals avilable for this, but I consider the caulk at least as

effective, and I had it on hand. When the bezel is twisted

on, some of the caulk extrudes out from under the bezel. This

is easy to trim off with an Xacto knife, and it indicates a good

seal. I wish I'd had the caulk in black, but I didn't want to

wait for it.

I was able to get the voltmeter to indicate pretty accurately, but

there are other sources of error. There is hysteresis for

one: the gauge reads differently when the voltage is

decreasing than when it is increasing. It's probably due to

slop in the mechanical linkage to the pointer.

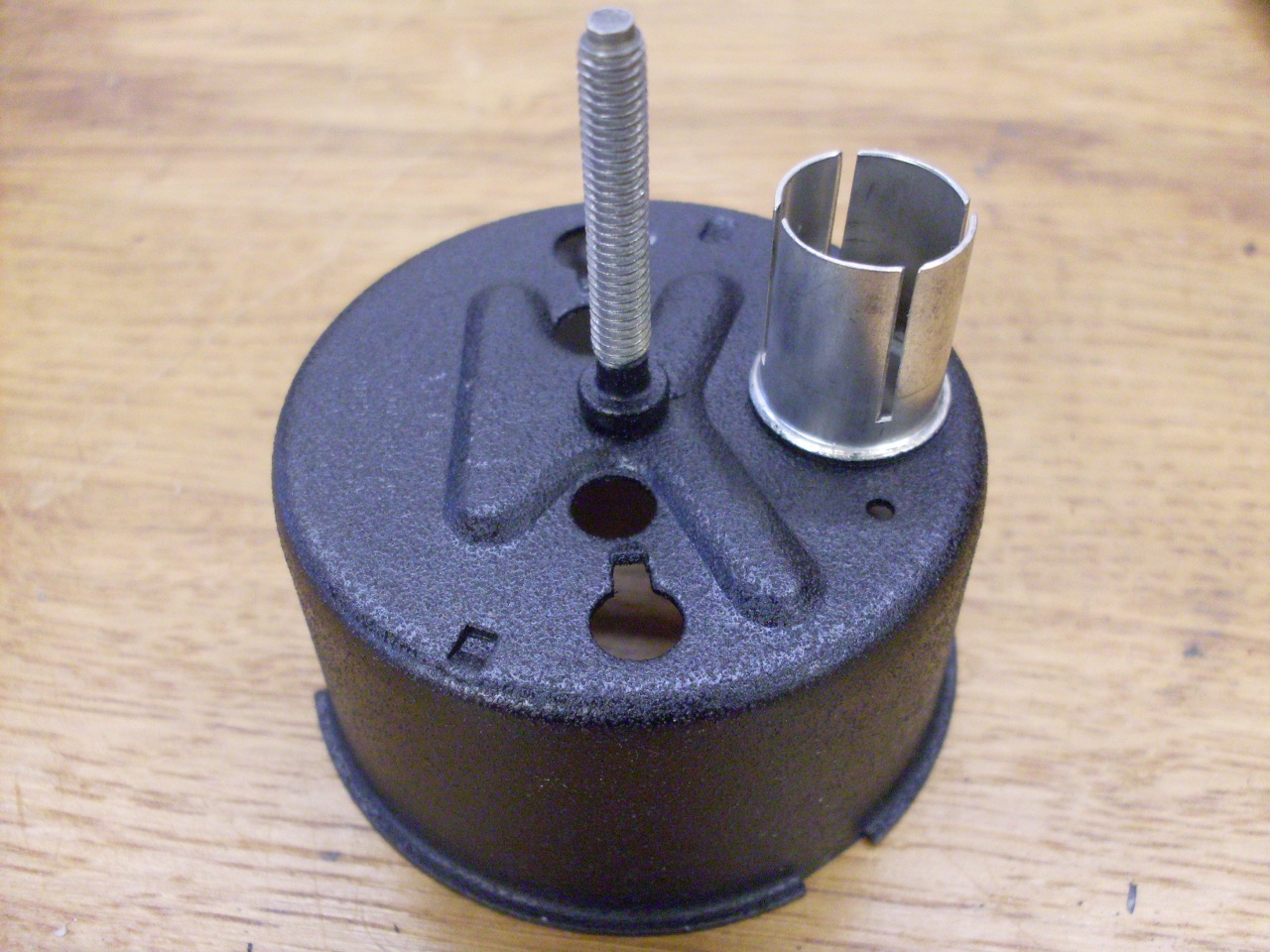

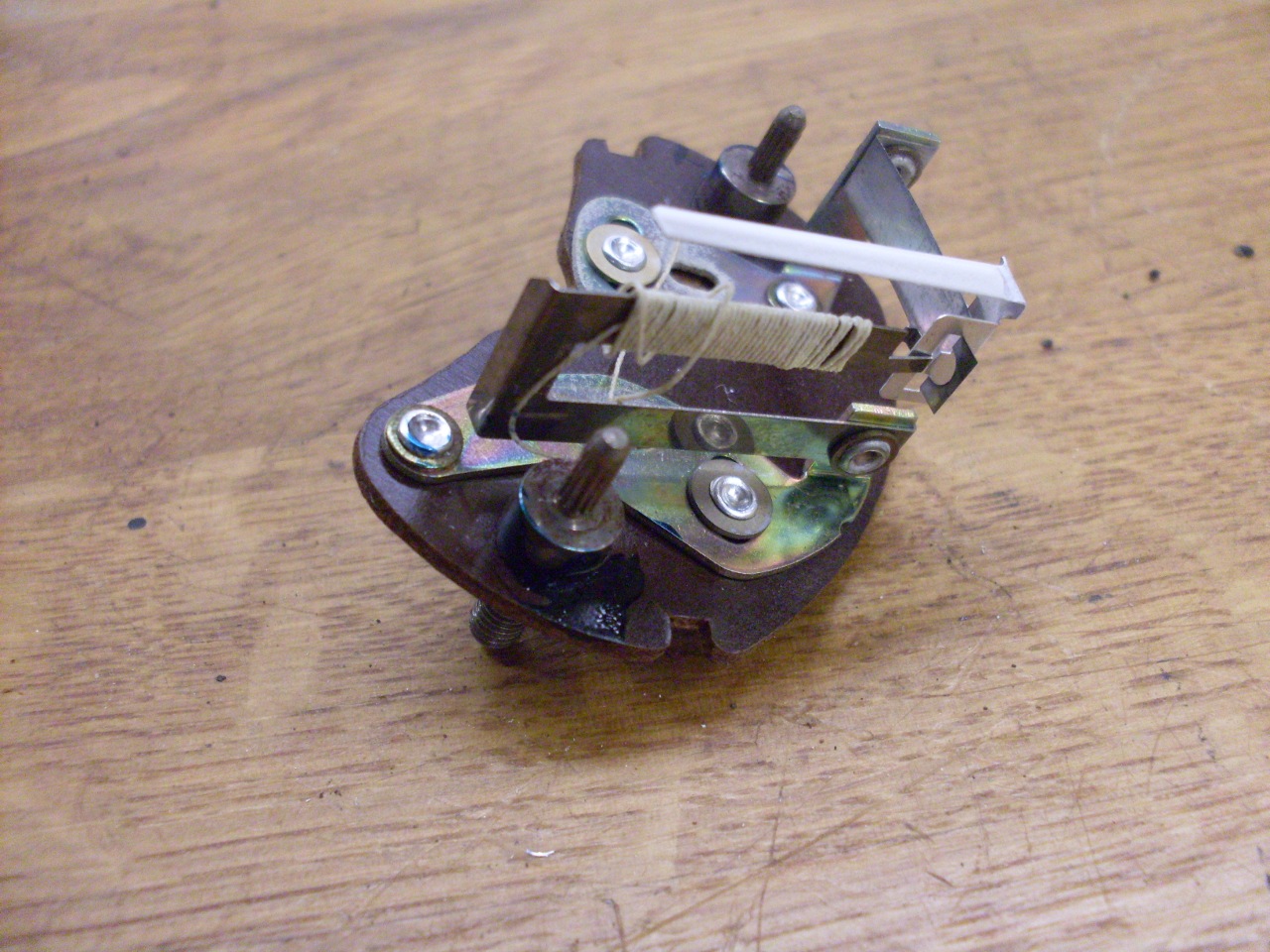

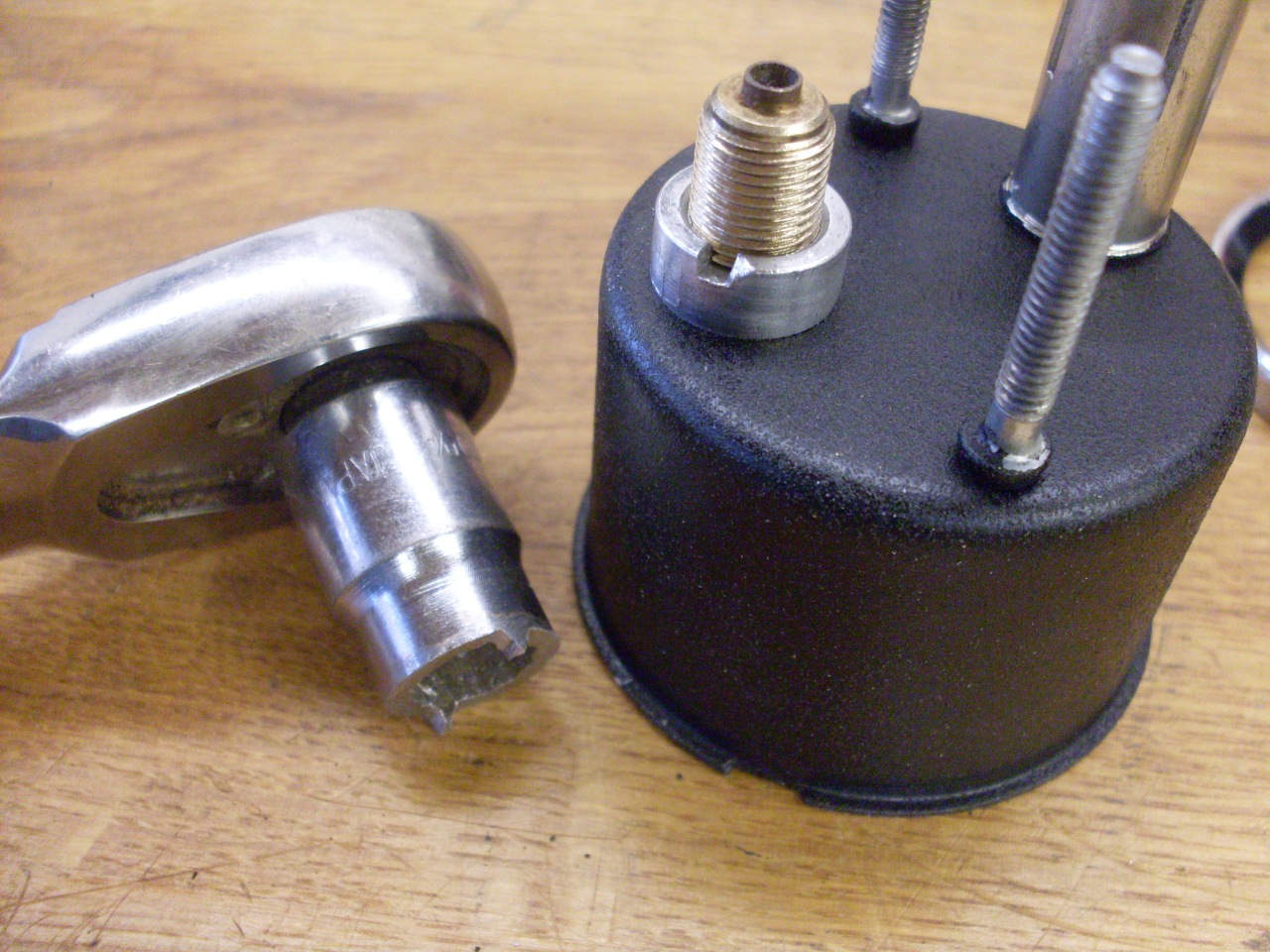

The oil pressure gauge is not the same as the other gauges inside.

It is a fully mechanical gauge based on a Bourdon tube, which

is a curled, flattened tube that wants to straighten out when

pressurized. A linkage mechanism amplifies and

transmits the motion of the tube to the pointer.

The oil gauge pointer was pretty yellowed, so I repainted it and all

the other pointers white so they would match.

This is a little spanner tool to remove and replace the nut on the back

of the oil gauge.

The parts pof the oil gauge, showing the illumination filter strip.

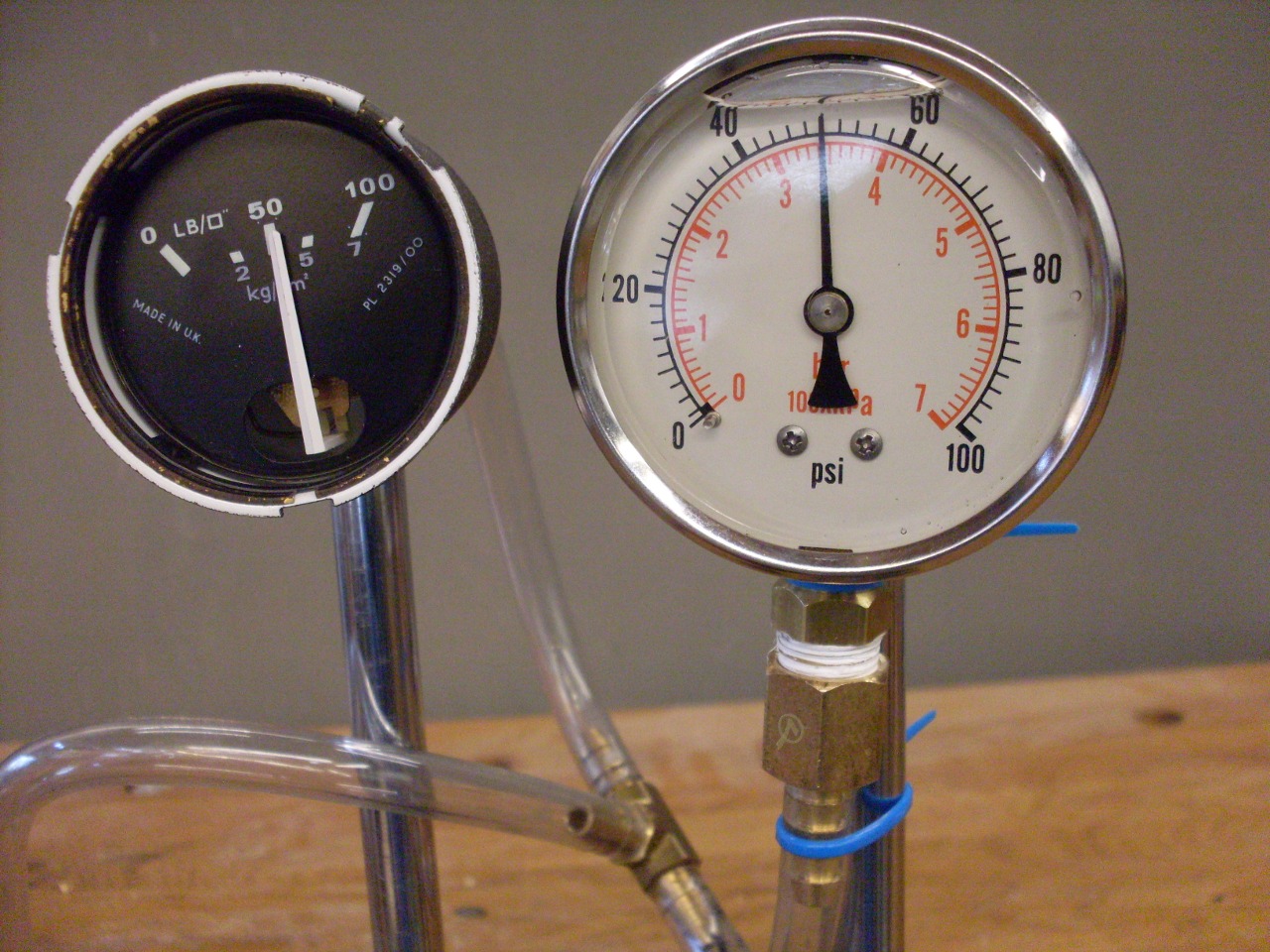

Checked calibration on the oil gauge. It was very close.

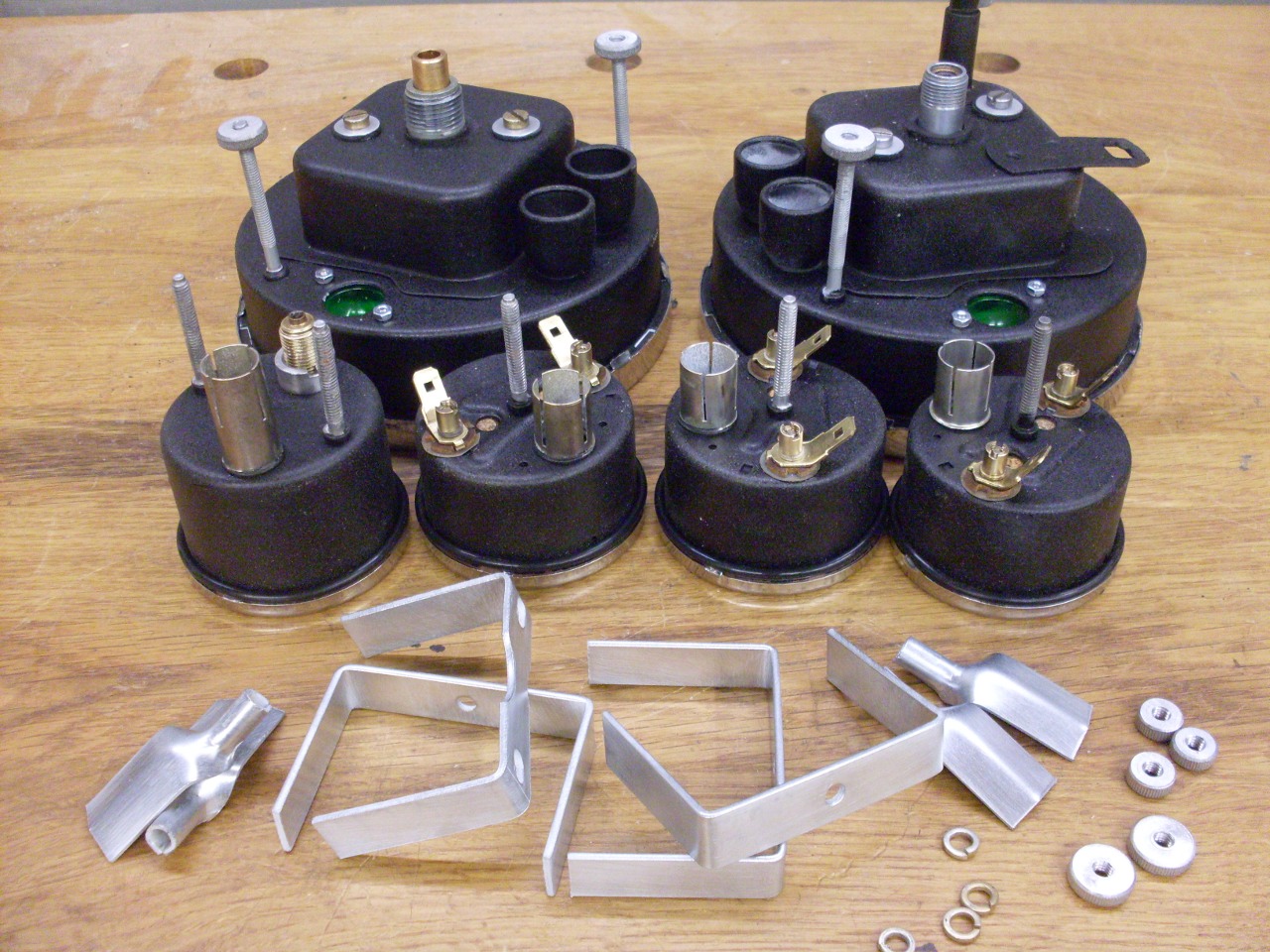

Replated the mounting hardware, and these go on the shelf with the speedometer

and tachometer

while I see to a new dash.

One interesting thing on the mounting hardware. The aluminum

finger nuts that secure the oil pressure gauge and the tach and speedo

all appear to be identical. They are not. The oil gauge nuts are

tapped 8-32, while the tach/speedo nuts are 3BA, which is a few

thousandths larger than 8-32, and 34.8 threads per inch. The nuts

can be forced onto the wrong stud, but the threads won't be happy.

Comments to: elhollin1@yahoo.com

To my

other TR6 pages