To my other TR6 pages

February 5, 2017

Seat Belts

My

car was fitted with 3-point inertial seat belts. This must have

been sort of a big deal back in the day, since I have seen some

early 70s ads bragging about it.

I

was a little overwhelmed at first when I dumped out the box with the

seat belts, until I realized there was a set of GT6 belts in there, too.

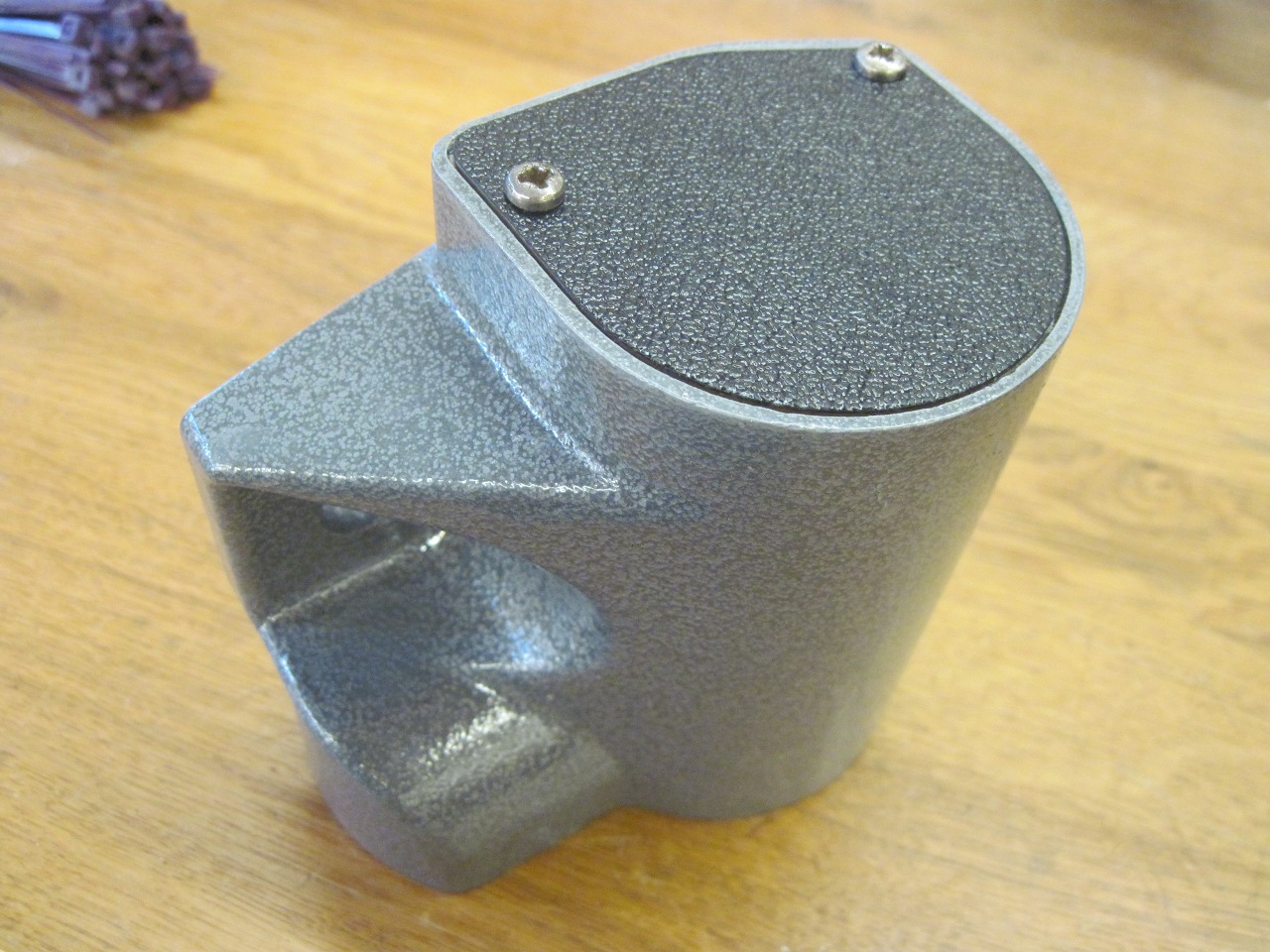

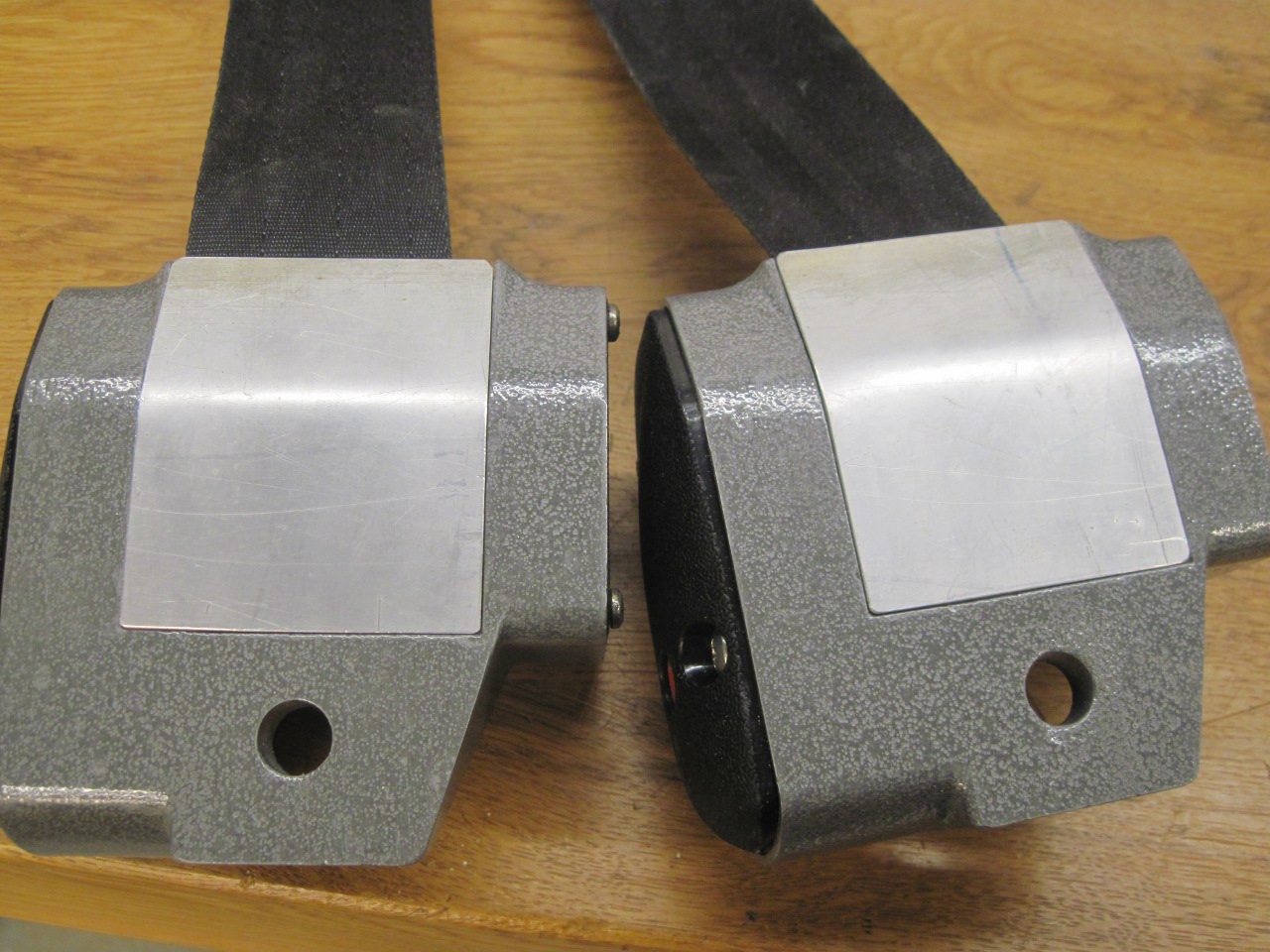

The

heart of an inertial system is a spring loaded reel which pays out the

belt freely except when there is a sudden motion of the car, in which

case it locks the reel. The reel, spring, latch, and acceleration

sensor are all in these aluminum housings mounted at the base of

the rear wheel wells. My units were dirty, crusty, and frozen.

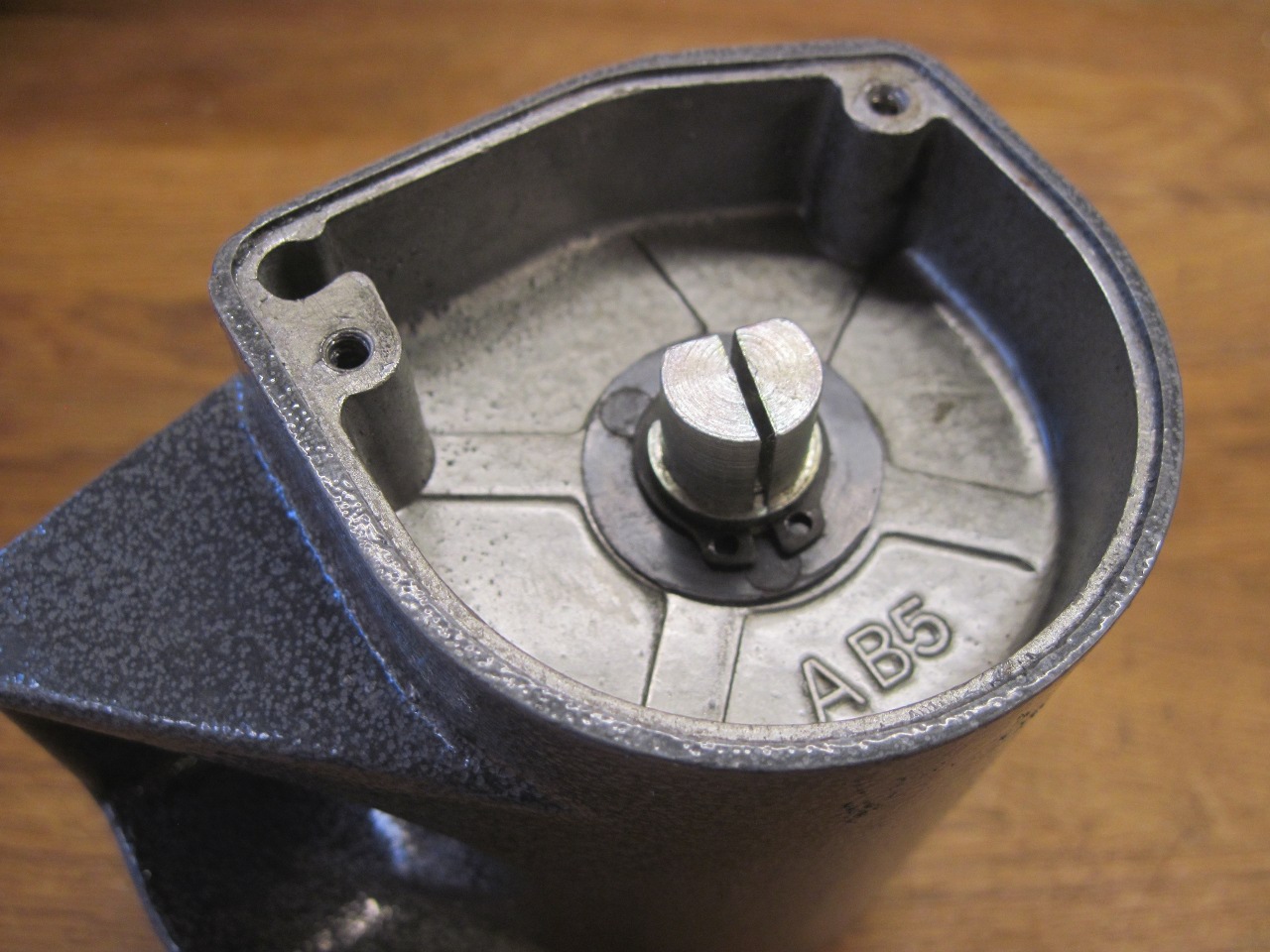

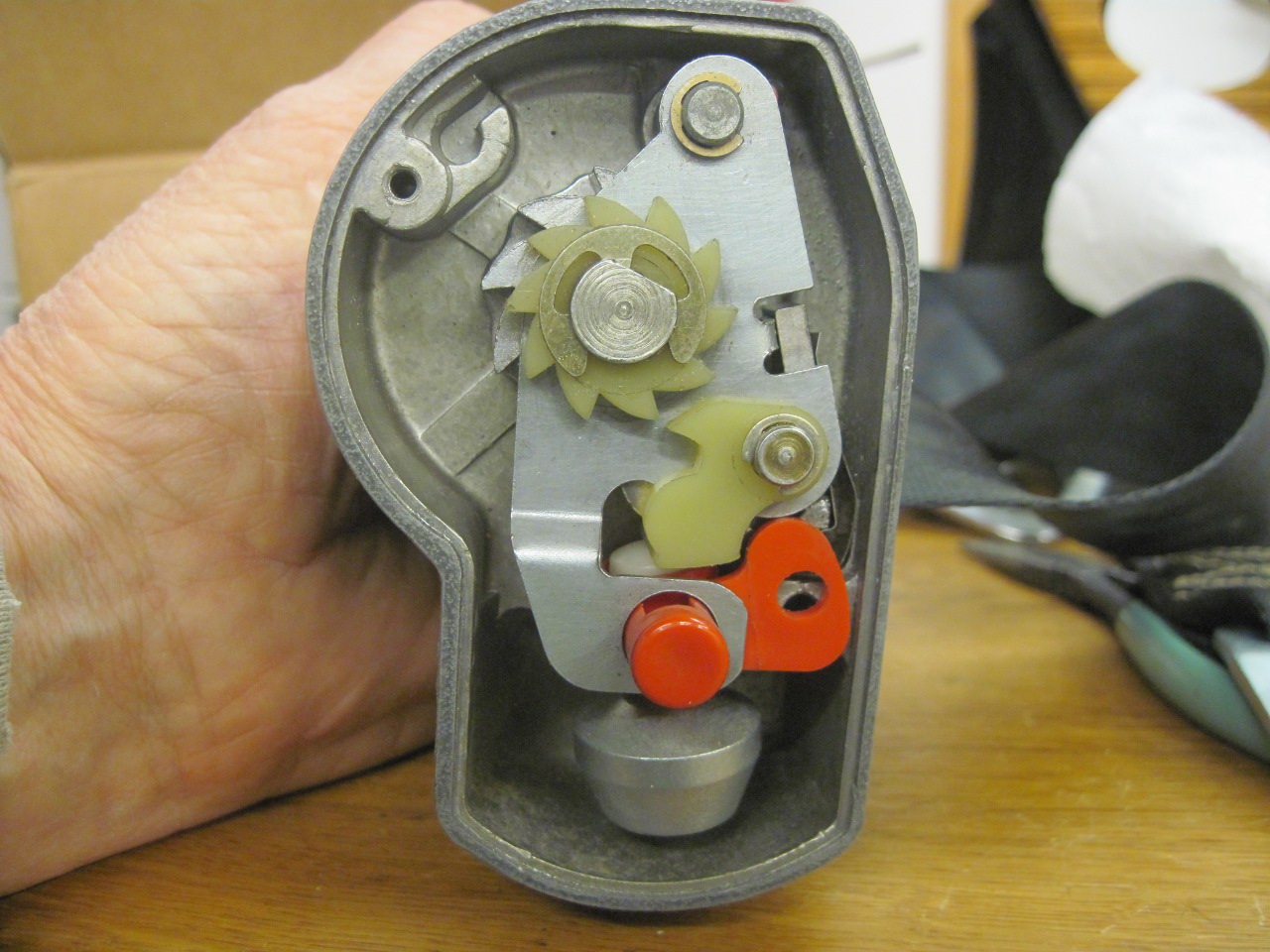

Under

the cover at one end of the unit is the sensor and latching mechanism.

The sensor is just a weight suspended from a plastic ball joint.

During any kind of acceleration, the weight's inertia will cause

it to deflect from vertical. When it does this, it slightly

raises a plastic lever so that a pawl on the lever catches one of the

teeth of a plastic ratchet gear tied to the belt reel. If there

is outward tension on the belt, the plastic gear will move the lever

further, such that it presses on a metal pawl which engages with the

main ratchet gear on the belt reel shaft.

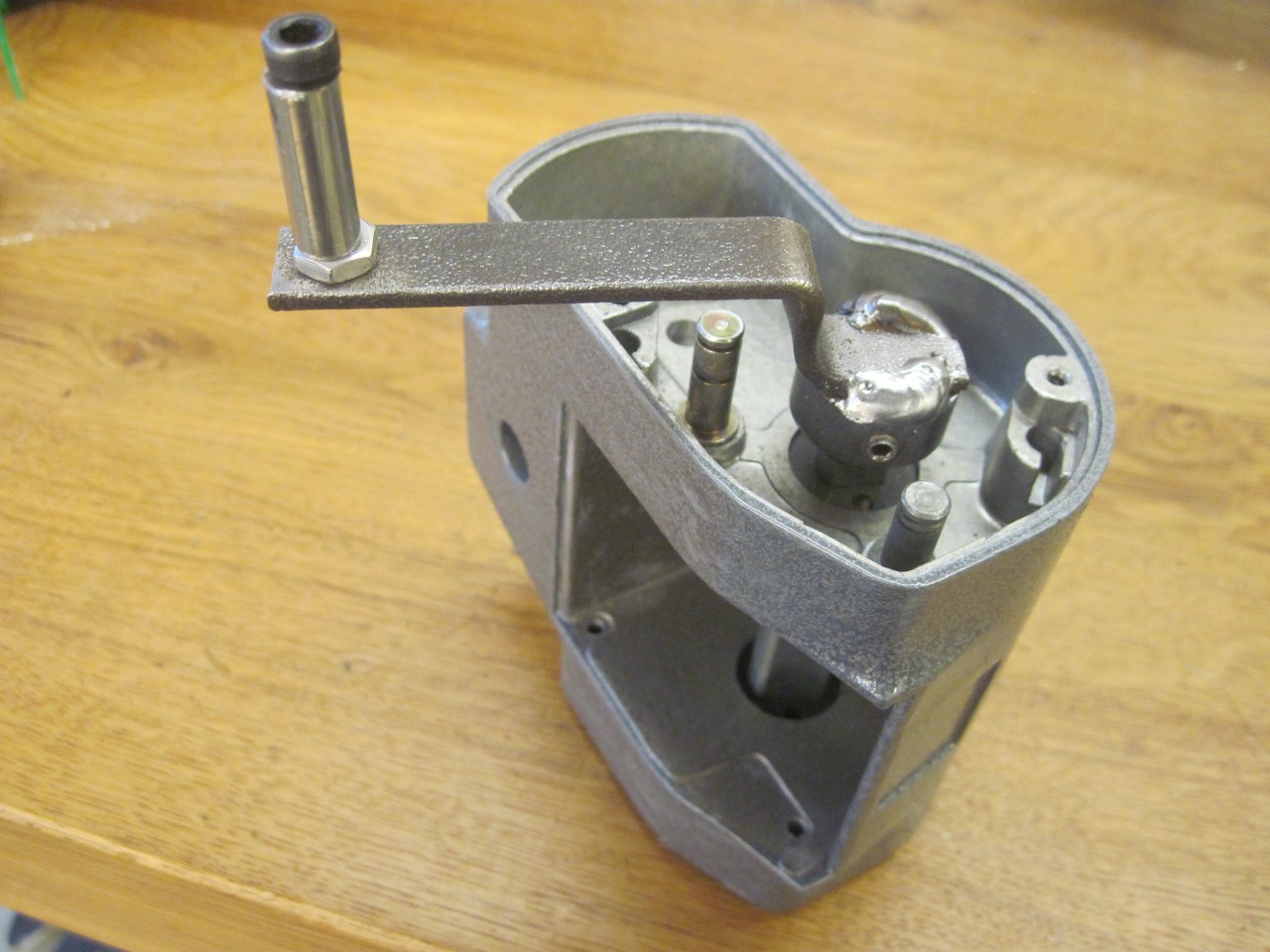

Under

the cover on the ther end of the housing is the reel spring. It is

a "constant force" spring, meaning that the torque it exerts isn't

affected much by how much it is wound up. This is due to the fact that

most of the turns of the spring are coil-bound, and only the free turns

in the middle section of the spring are active in generating force.

If I lifted my thumb off the spring, it would instantly

escape in a frenzy of exuberant springy energy.

To

disarm the spring, I pulled all of the webbing out of the reel housing.

This exposes a pin that captures the end loop on the belt to the

reel spindle. Removing that pin frees the belt from rotating with

the spindle. Before pulling the pin, I put a clamp on the spindle

so I could control the unwinding of the srping. Mainly, I wanted

to count how many turns it took to relax the spring so I'd know how

much to wind the spring up in case I was lucky enough to get everything

back together again.

The relaxed spring comes out with its own little plastic carrier.

With the spring and other parts gone, the actual reel spindle can be removed.

With everything now taken apart, it was time to inspect and renew parts as necessary.

The pendulum assembly seemed mostly OK, but the weight was really corroded and had flaking plating.

With some new plating and a new tubular rivet, it looked a lot better.

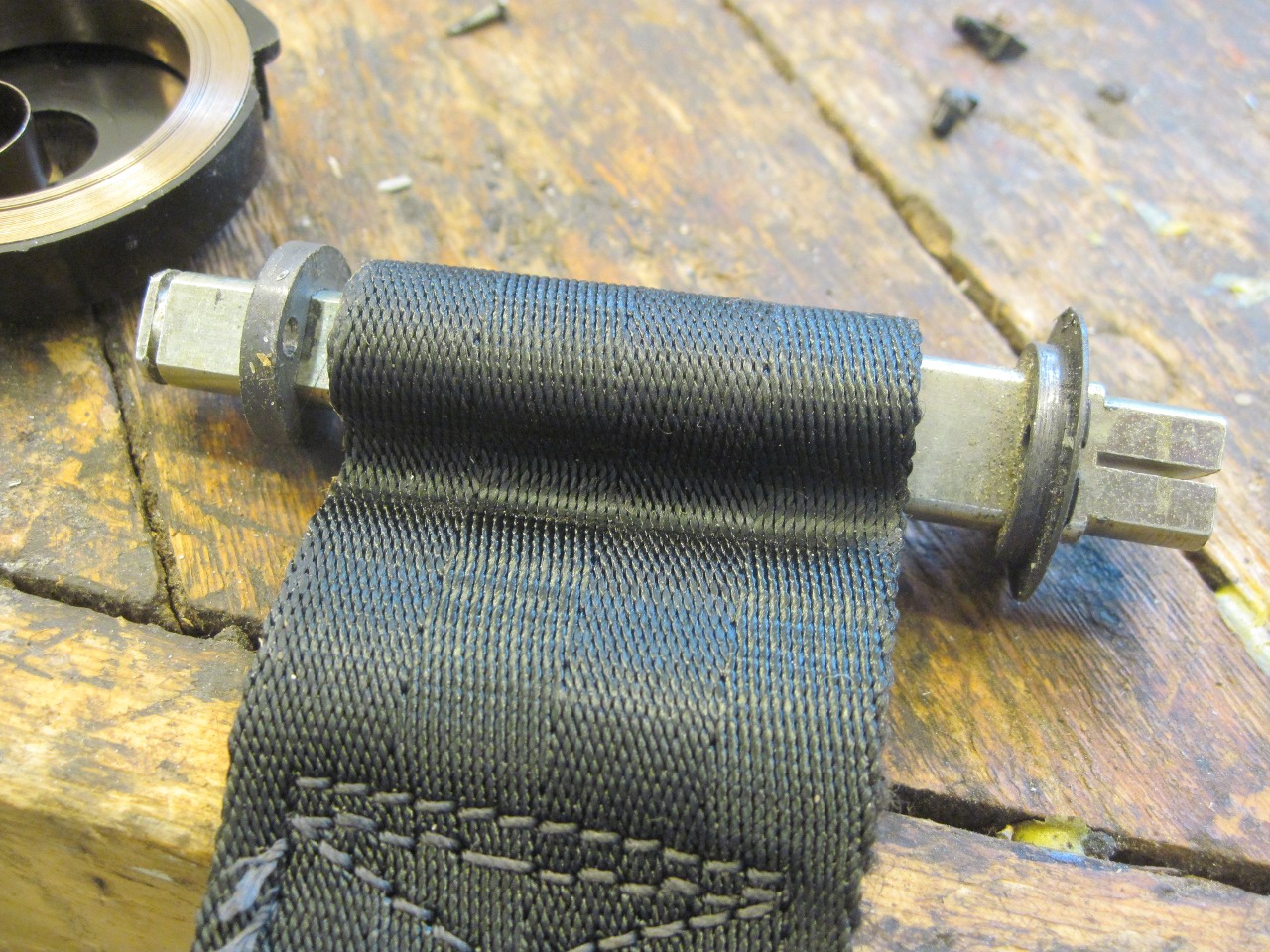

Next

up was the webbing and its various fittings. Some of the

fittings were a real mess. The worst of them were stitched into

the webbing, so the web would have to be cut or unstitched to get at

them for renewal. I unstitched the end fitting since I hadn't decided whether I was going to try to reuse the webbing.

The fitting cleaned up and plated nicely.

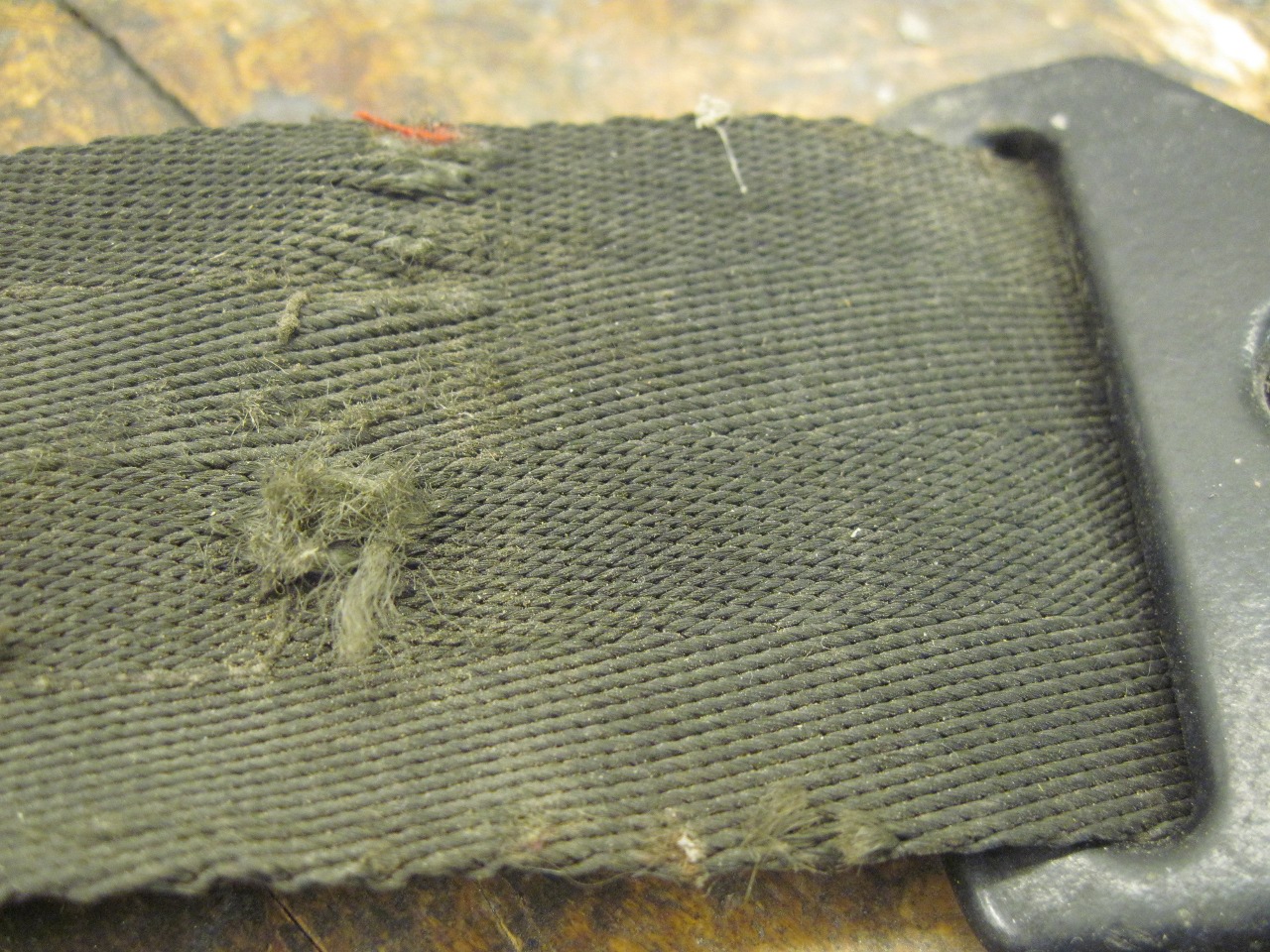

On closer inspection of the webbing, I really had no choice. It was dirty and faded, and in places, it was pretty worn.

So I bought some seat belt webbing. Now the only problem is that I don't sew.

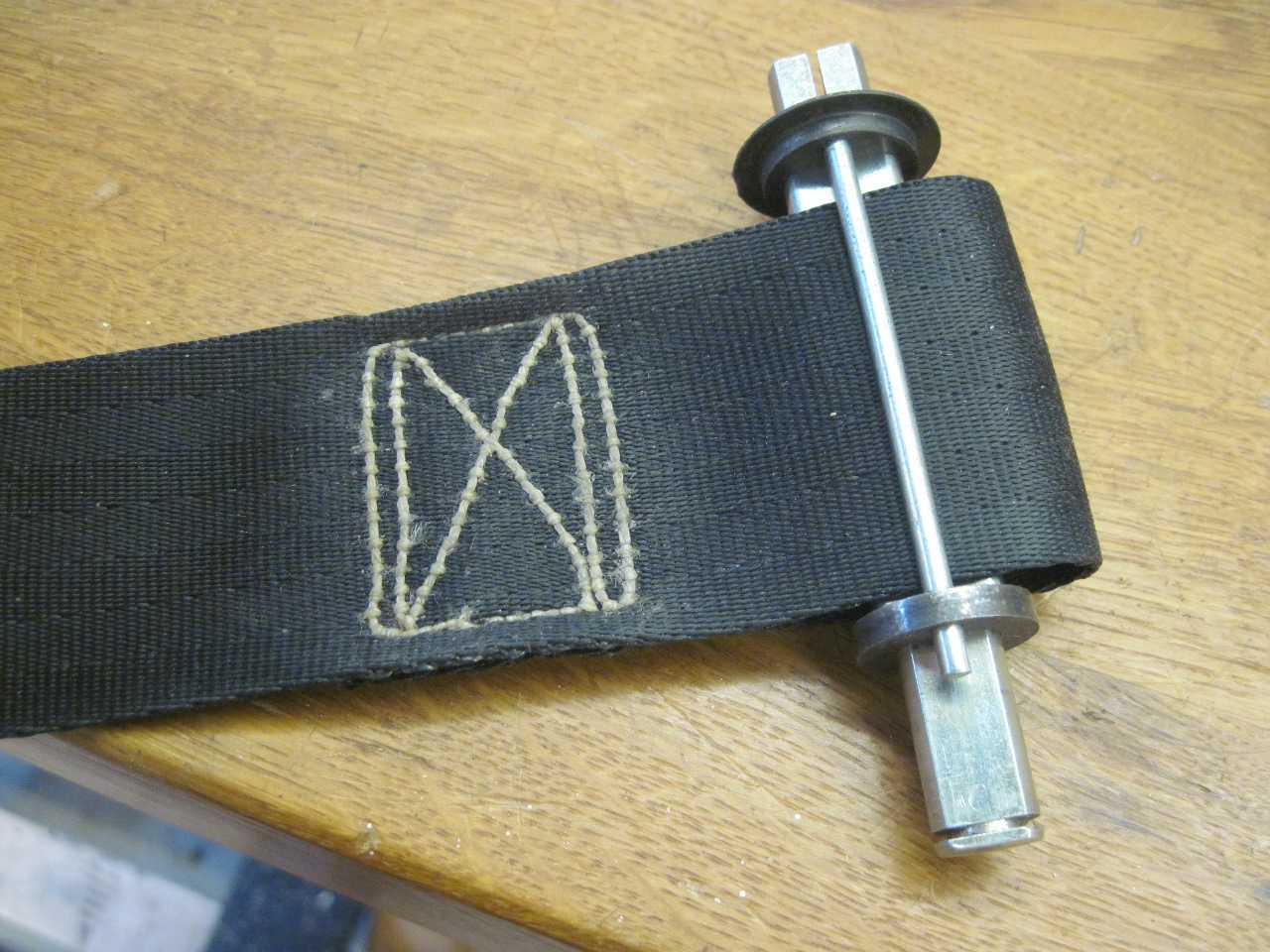

Well,

I didn't sew, but I guess I do now, sort of. I didn't really want

to invest in a sewing machine, especially a heavy duty one man enough

to sew multiple layers of this webbing. Some research revealed to

me that sailors sometimes have to repair their canvas sails without

benefit of a machine, and there may even sometimes be places on a sail

that a machine can't reach. In these cases, they are forced to

revert to the ancient art of hand stitching. Pictured below is one

tool apparently popular in sailing circles. It makes a lock

stitch, just like a machine, but slower. I sewed up a few

practice pieces and eventually decided that I was certinly no Betsy

Ross, but I could make a strong seam. I definitely got better as

I went.

So

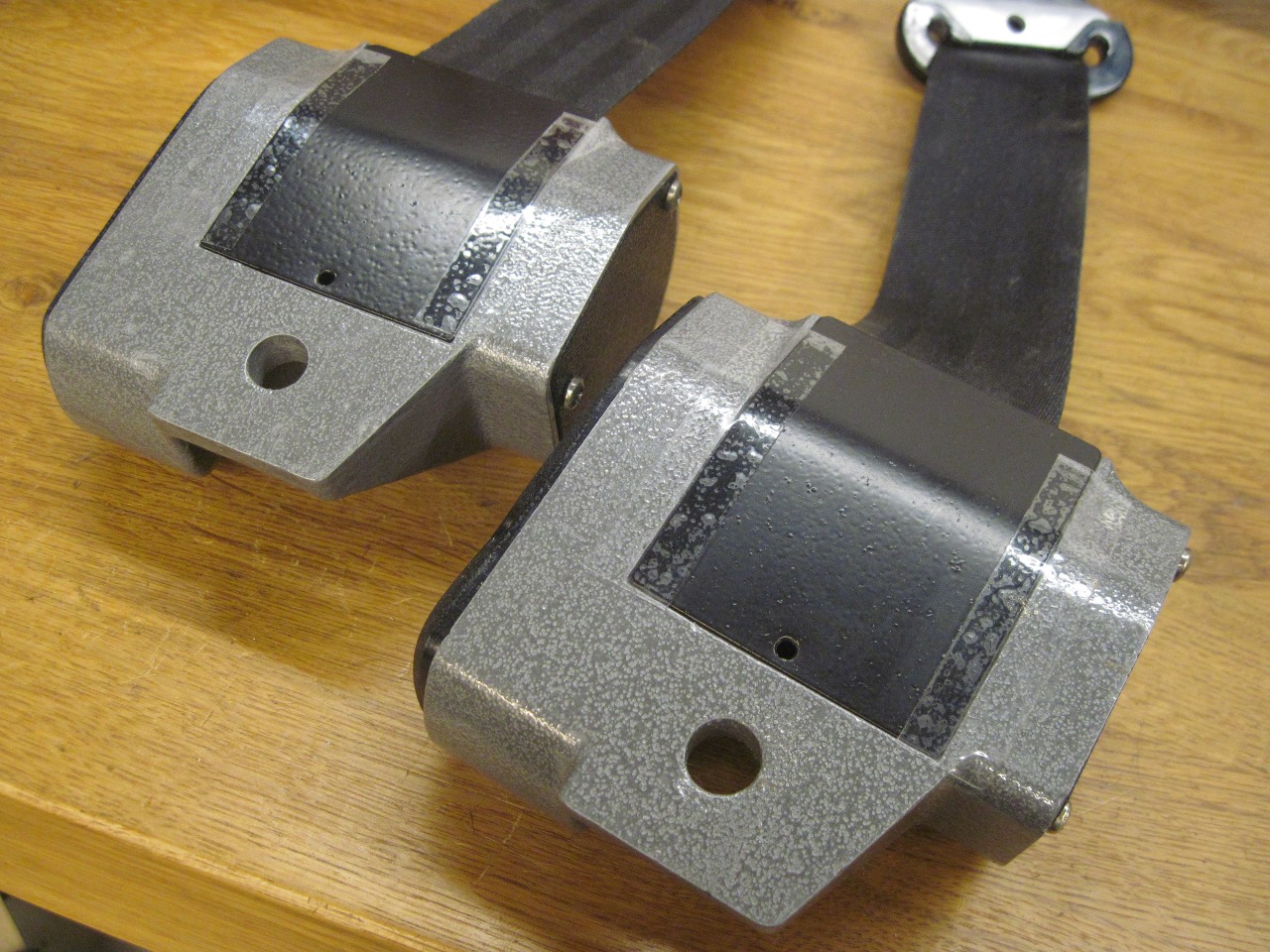

with most of the component parts renewed, it was almost time to

reassemble. Just needed to make the main housings more

presentable.

I

bought some silver hammertone powder coat powder. It turned out

to be darker and more contrasty than the original hammertone paint, but

I'm not going to fret about it.

I was even able to clean up and reapply the original manufacturer's logo.

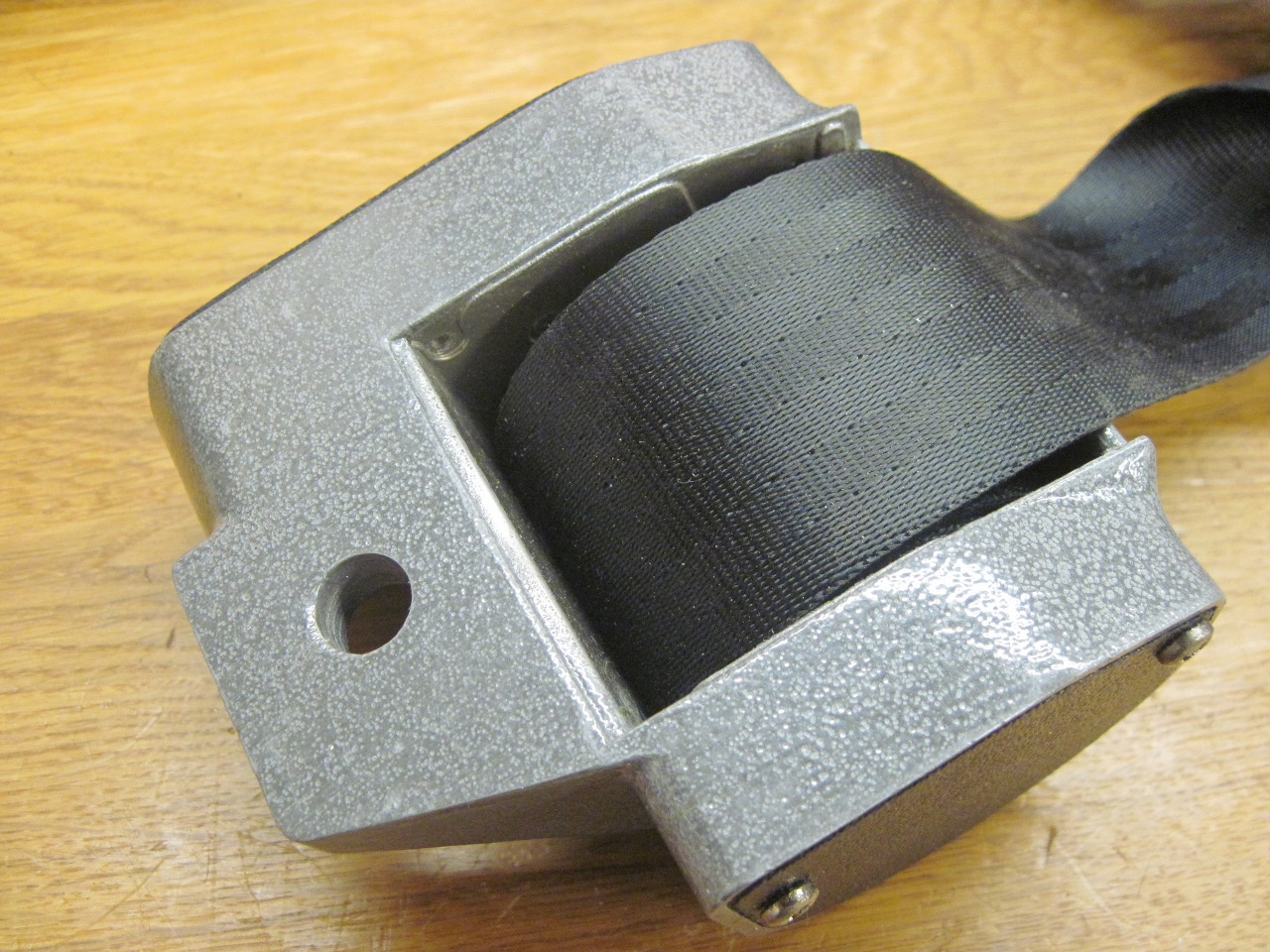

Installed the spindle and the spring and cover plate.

Then,

to wind up the spring, I made this little crank thingy that fits over

the end of the spindle. The picture doesn't show it, but the end

loop of the webbing has to be installed on the spindle before

tensioning the spring.

I

gave the spring about 20 turns to wind it up, inserted the keeper pin

to capture the web, and let the web slowly wind back onto the spindle.

It only takes about 12 turns for the web to fill the reel cavity

and stop.

Now on to the inertia mechanism. I applied some light grease in places where I found dried up grease on disassembly.

Put

the cleaned up cover back on, and this dude is pretty much done.

I still wonder why the mfr made that red plastic piece looks so

much like a pushable button.

Now just have to do the other one.

I

realized after I was done with both units that there was originally a

plastic cover piece on the back side of the reel housing. I found

the broken cover in the bottom of the box the belts were in. The

cover attaches by a fragile little pin at each corner that fit into

tiny holes in the housing.

I'm

not sure this cover is really that necessary, but I wanted complete

closure. I made a couple of aluminum plates that fit pretty

snugly. I didn't think I could recreate the pin mounting

arrangement (that didn't really work that well anyway), so at least for

now, I just fixed the covers in place with strips of packing tape.

On the shelf with these guys.

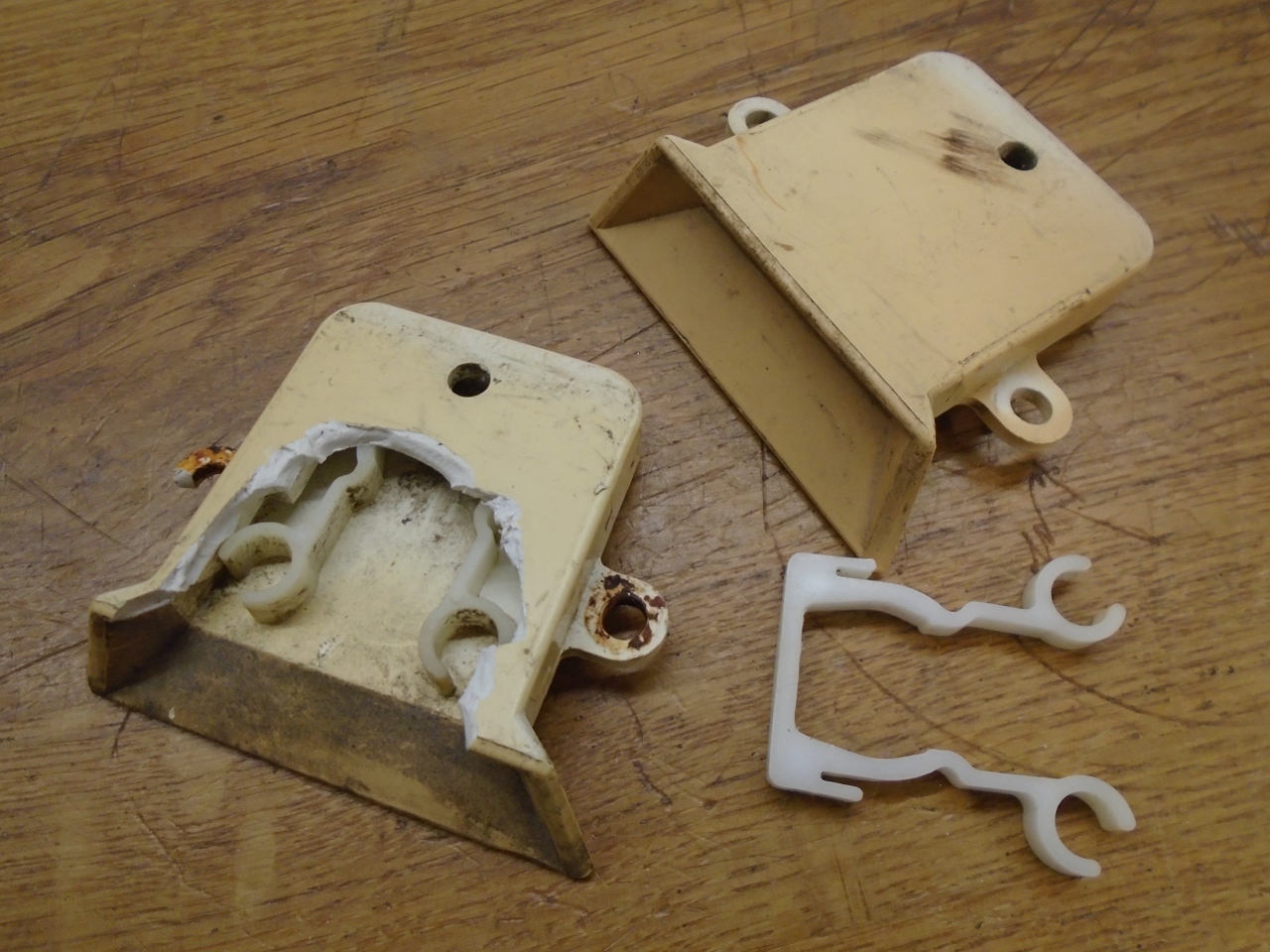

Though

the inertial mechanisms are done, there is another part of the seatbelt

system. There is a latch mounted on a stalk that sticks up on the

inboard side of each seat. The latch accepts the tang on the

seatbelt and hold it securely until the release button is pushed.

One of my latch pieces had some violence in its history.

Now

I can fix a lot of things, but I just didn't see any practical way to

fix that plastic shell. I looked online for some stalks for sale,

but didn't find any available by themselves. Next, I appealed to

the LBC community on one of the popular forums. A gracious and

generous member sent me a couple of sets of stalks.

The

stalks were not from a TR6, but a Jaguar, I believe. They were

very similar to mine, but did have some differences. The most

significant difference was the actual stalk part that the latch

mechanism attaches to. The new parts had shorter stalks with a

different mounting angle.

Now

on the original parts, the latch connects to the stalk with a roll pin,

and the pin is accessible through a plugged hole on either side of the

latch shell.

Unfortunately,

the new parts didn't have the access holes. Assuming the innards

of the new parts were the same as the old, at least in how the latch

attached to the stalk, I drilled a small exploratory hole.

Bingo--the roll pin was right where I hoped it would be. I

enlarged the hole and drilled one on the other side so I could drive

the pin out. Then attached the original stalk to the new latch

and plugged the holes with the original plugs.

Can't wait to install these.

This

was a fairly involved project, but pretty cheap. Though

aftermarket seatbelt systems are available and reportedly work well,

I'd probably do this again given the chance. At least my sewing

would be better on the next one.

Update: May 19, 2018

Seatbelt Parkers

Pawing through one of the few remaining boxes of random parts, I found these.

It

was a mystery at first--I didn't recognize them at all. It turns

out that they are seat belt "parkers". They screw to the inner

sills on either side of the car, next to the seats. They were

there to accept the tangs of the seatbelts to keep them handy. I

can't remember ever using them, but since I had them, I thought I'd see

about fixing them up.

Inside

each white plastic housing was a plastic spring. The springs were

retained in the housings with little tabs with pips that fit into the

holes seen near the bottom of the housings. I depressed the tabs

to remove the springs, and promptly broke both of them off. At

this point I was already considering making new housings, so I chewed

away at one of the parts to get better measurements from the inside.

This

seemed like a good application for 3D printing, so three or four

iterations later, I had some printed ABS housings that matched the

originals pretty closely. The new housing is in two pieces that

will be glued together. I re-used the original springs, but

had to retain them in a different way since the tabs were missing.

The last pic is the housings snapped together, but no cleanup of

the edges yet.

Looks like they are going to work OK.

This

little exercise was more about learning CAD and 3D printing than car

restoration, but unlike much 3D printing, it produced something at

least marginally useful.

Comments to Ed at elhollin1@yahoo.com

To my other TR6 pages