To my other TR6 pages

November 18, 2015

Brake Servo

All

TR6 cars had power assist brakes. The power comes from engine

vacuum collected from the intake manifold and stored in a reservoir in

the brake servo unit. The servo unit fits between the brake pedal

and the brake master cylinder so that it can both sense pedal position

and also augment the force applied to the master cylinder.

The

servo unit on a TR6 is another one of those devices usually considered

not to be a DIY item. While these kinds of warnings amuse me, the

servo is a little different. Even if a determined person manages

to get inside the unit, none of the internal parts appear to be

available from retail suppliers. There are commercial outfits who

will rebuild the servos, so they apparently have the parts custom made

for them. Before laying a hand on my servo, I contacted one of

these rebuilders about the possibility of buying internal parts,

particularly the main diaphram. They declined to sell me

anything, citing "liability concerns", which doesn't ring true to me.

It seems to me that rebuilding or otherwise supplying entire

brake servos would imply as much or more liability risk.

At any

rate, I decided to forge ahead. If I got to the point where the

servo would be junk without some new innards, I could still just bag

everything up and send it off to a rebuilder. Even if it came to

that, I could still powder coat the cases myself and save a little coin.

There is a wonderful resource on the Web for anyone considering opening a servo. The technical pages at buckeyetriumphs.org

are a goldmine of information for many aspects of the TR6, including

the servo. I'm indebted to the folks at Buckeye for providing

this valuable asset.

Commensurate

with the rest of the car, my servo was a greasy, dirty, rusty lump.

Notice the debris inside the nose around the fork. That is

the remains of a filter. More on that later.

There

are a few things that can be easily taken off the unit--the spacer, the

dust cover, and with a little more dermination, the front seal and the

"non return valve" where the hose from the manifold connects.

But for the really interesting stuff the case has to be

opened.

The case is in two halves, joined by a bayonet

style joint. The circumference of the internal rubber diaphragm

is captured in the joint and is under considerable compression, so the

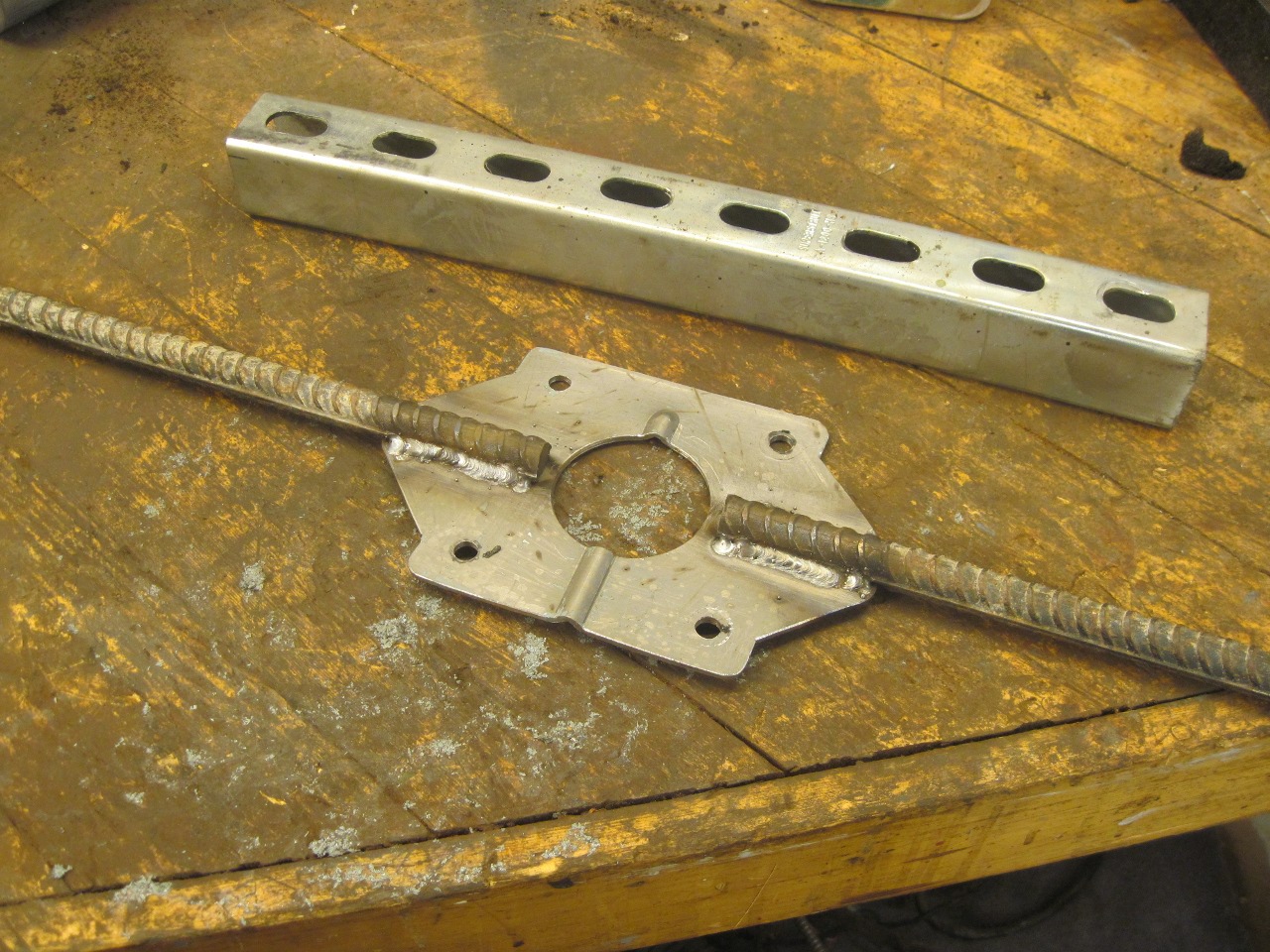

joint isn't a pushover. I made some tools similar to those

described on the Buckeye site.

With

a cheater bar and some enthusiastic hammer work, the joint finally gave

up. Imagine my happy surprise when I removed the internal

diaphragm/carrier assembly and saw that the inside of the cases were in

pristine condition! Other than some congealed 40 year old grease,

the inside surfaces looked brand new.

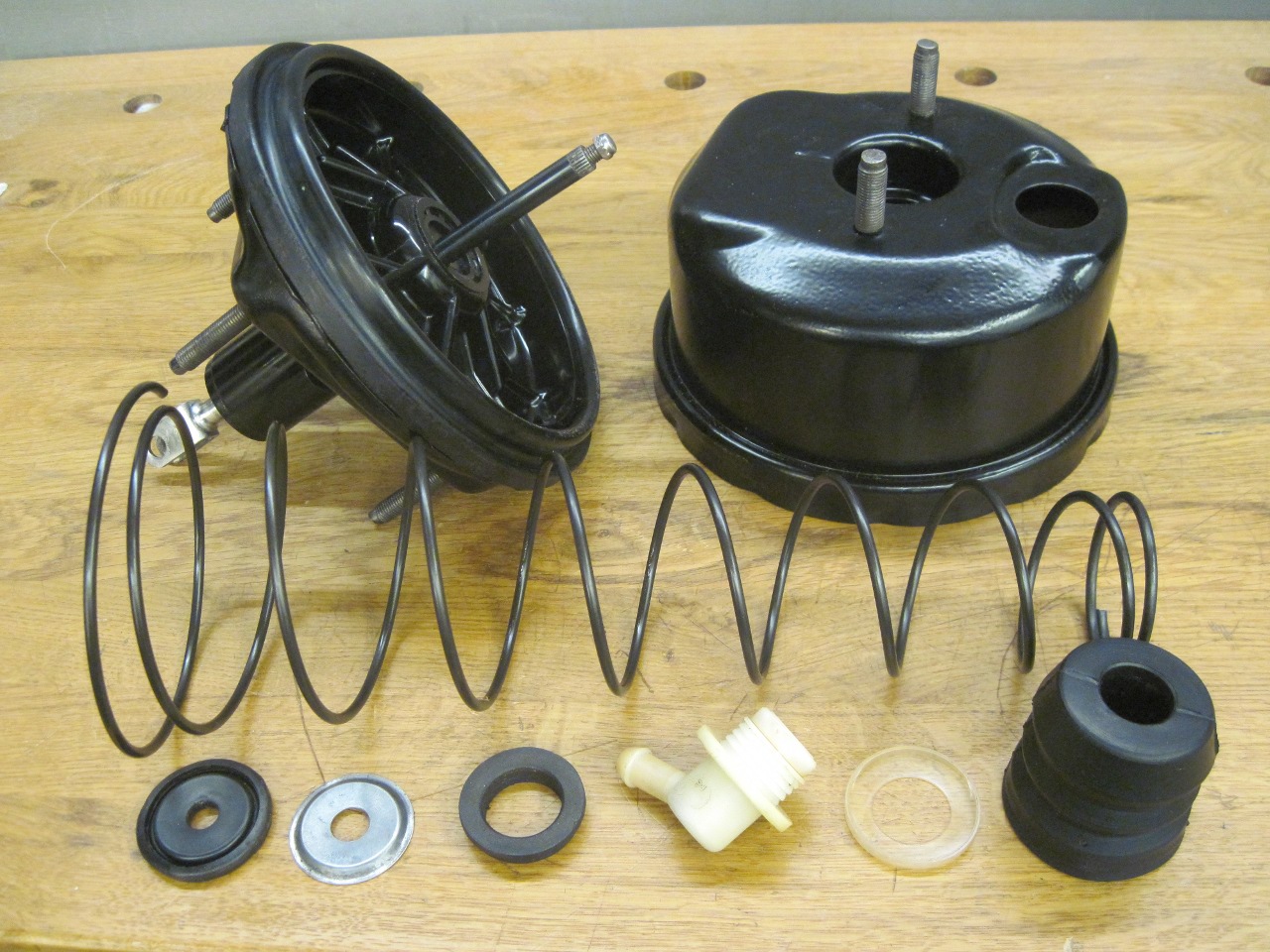

Encouraged,

I turned to the internal parts. The large rubber diaphragm is

carried by a large plastic (phenolic, I think) carrier. Inside

the central bore of the cerrier is a valve assembly. The valve

assembly is located and retained in the bore with the little forked key.

The

diaphragm appeared to be intact, and was still very supple, but had an

uneven surface coating. I'm guessing it was the parting compound

from the molding process. After a little cleanup, it looked much

better. I couldn't see anything wrong with the diaphragm.

The

valve assembly appeared to be staked together so I didn't disassemble

it. I believe when these were available, they were sold as a

unit.

There are two rubber parts in the assembly.

One acts as a seal inside the bore of the diaphragm cerrier, and

the other seats on an opening in the carrier that connects the chambers

on either side of the diaphragm. With the brake pedal not

pushed, the volumes in back of and in front of the diaphragm are

connected, so that the engine vacuum evacuates both chambers.

When the pedal is pushed, first the valve assembly closes off the

connection between the two chambers, and then opens the rear chamber to

atmospheric pressure through the cetral bore in the carrier. The

imbalance in pressure pushes the carrier forward, adding force to the

pedal force.

The

bore in the carrier was shiny and smooth, and the valve assembly

seemed to still be a nice fit. A little rubber preservative made

the diaphragm look even better. I was pretty encouraged at this

point.

I cleaned up the outside of the cases and powder coated them with a semigloss black.

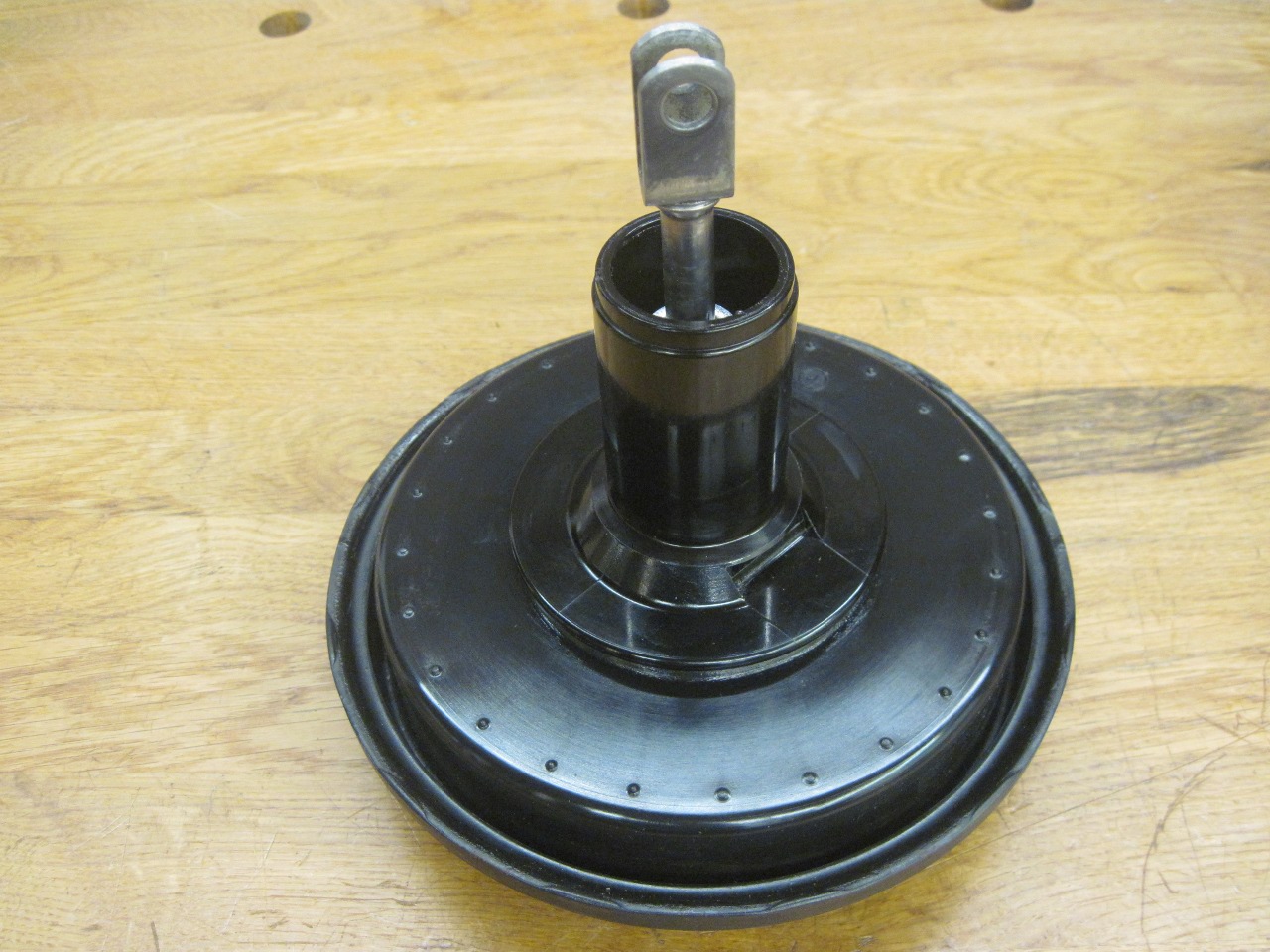

This

assembly seals around the neck of the diaphragm carrier. Again,

the cleaned and lubricated rubber seemed to still be a good fit.

The rest of the parts, all original.

This

dust cover is one of the parts that is available for the servo, but

after I cleaned it up, I could see no reason to replace it. It

was still pliable, and a good fit on the case. If I got this

cover in the mail as a replacement, I would be totally satisfied with

it.

The

cases went back together much easier than they came apart. Some

rubber lube on the diaphragm circumference helped a lot. The

white pads protect the paint. I tested the check valve before I

put it back in.

The

last item was the filter inside the nose of the carrier. It

filters the air drawn in to the rear chamber when the vacuum is

released. It was the only really perished part of the entire

servo. It is not available anywhere that I could find. In

the end, I bought a piece of 1" thick polyurethane open cell filter

media, and cut a cylindrical piece out of it. It doesn't look too

far off from what's left of the original in the middle picture.

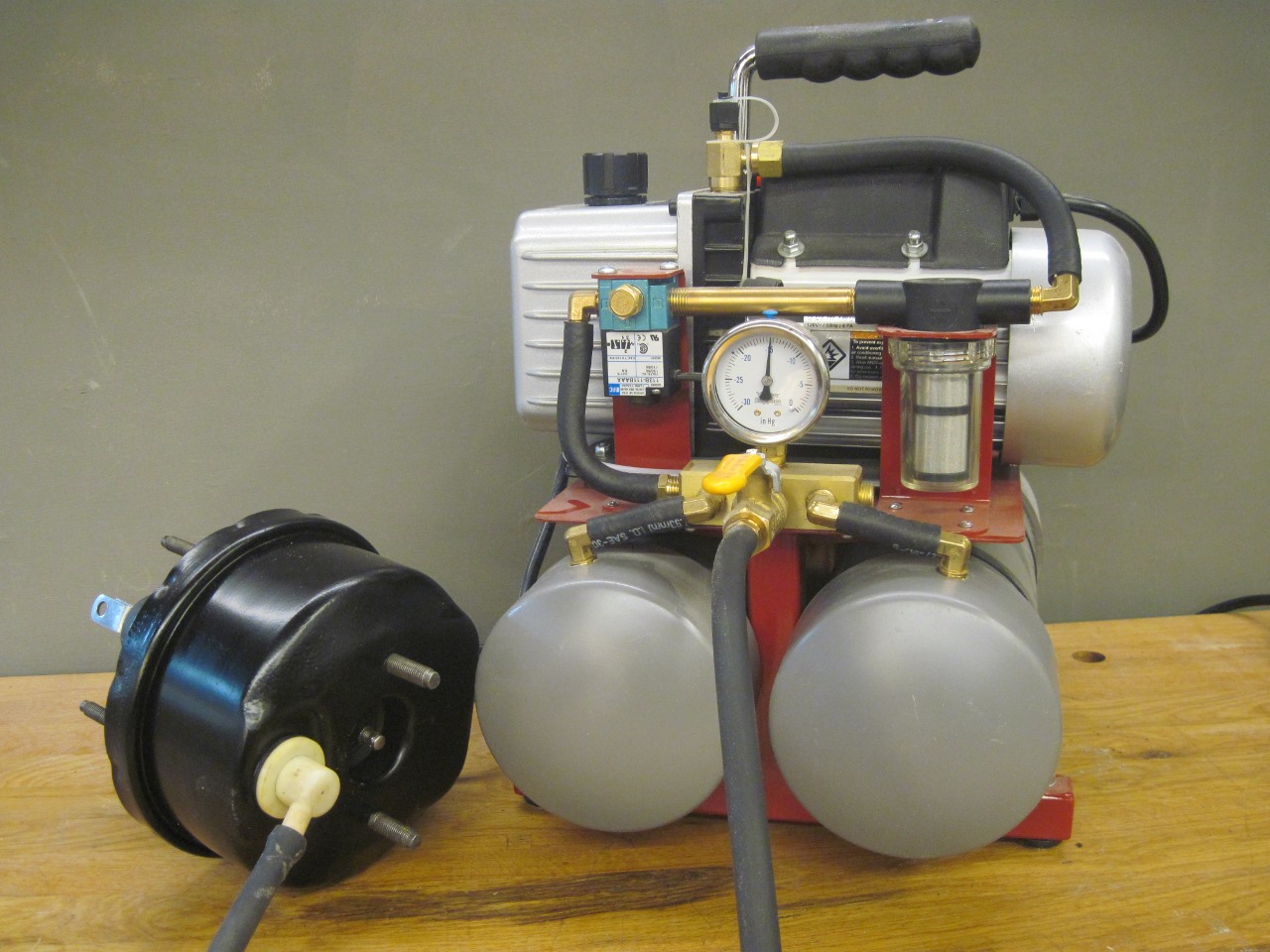

So

here is the critical question: Can all of these 40+ year old

rubber parts still contain a vacuum? I pumped the unit down to 15

inches of vacuum, and turned the pump off. It looked pretty

steady. One hour later, the vacuum was a little under 14 inches.

In the interest of full disclosure, I will point out that since I

didn't have another vacuum gauge, I left the valve from the pump open

so I could use the pump's gauge. This added the pump's reservoir

volume to that of the servo, so it's possible that the servo alone

might leak down a little faster. I was hesitant to actually

actuate the servo because I wasn't sure how it would react without the

load of a master sylinder attached.

I

really couldn't have hoped that this exercise would have turned out

better. It is still hard for me to believe that these 40 year old

rubber parts are still doing the job so well. Total cost for the servo

was close to nothing. Some power coat powder, some silicone brake

grease, and $8 for the filter material.

Comments to Ed at: elhollin1@yahoo.com

To my other TR6 pages