To my other GT6

pages

September 19, 2020

Rear Damper Brackets

The earliest GT6 cars apparently had a simple swing

axle arrangement at the rear with a very typical tube damper

spanning from a stud on the vertical link to a bracket on the

frame. With the advent of the MK2 in 1969, the rear drive

design was upgraded to include a rubber "Rotoflex" joint at the

outboard end of each half-axle. While this did improve

performance, it also required that the top damper attachment be

relocated. The damper had to be swung outward to avoid

fouling the Rotoflex, and Triumph Engineers chose to create a new

top damper fixing point on the inside of the wheel well

itself. Many people feel that attaching a damper (and bump

stop, by the way) essentially to body sheet metal was a bad

design.

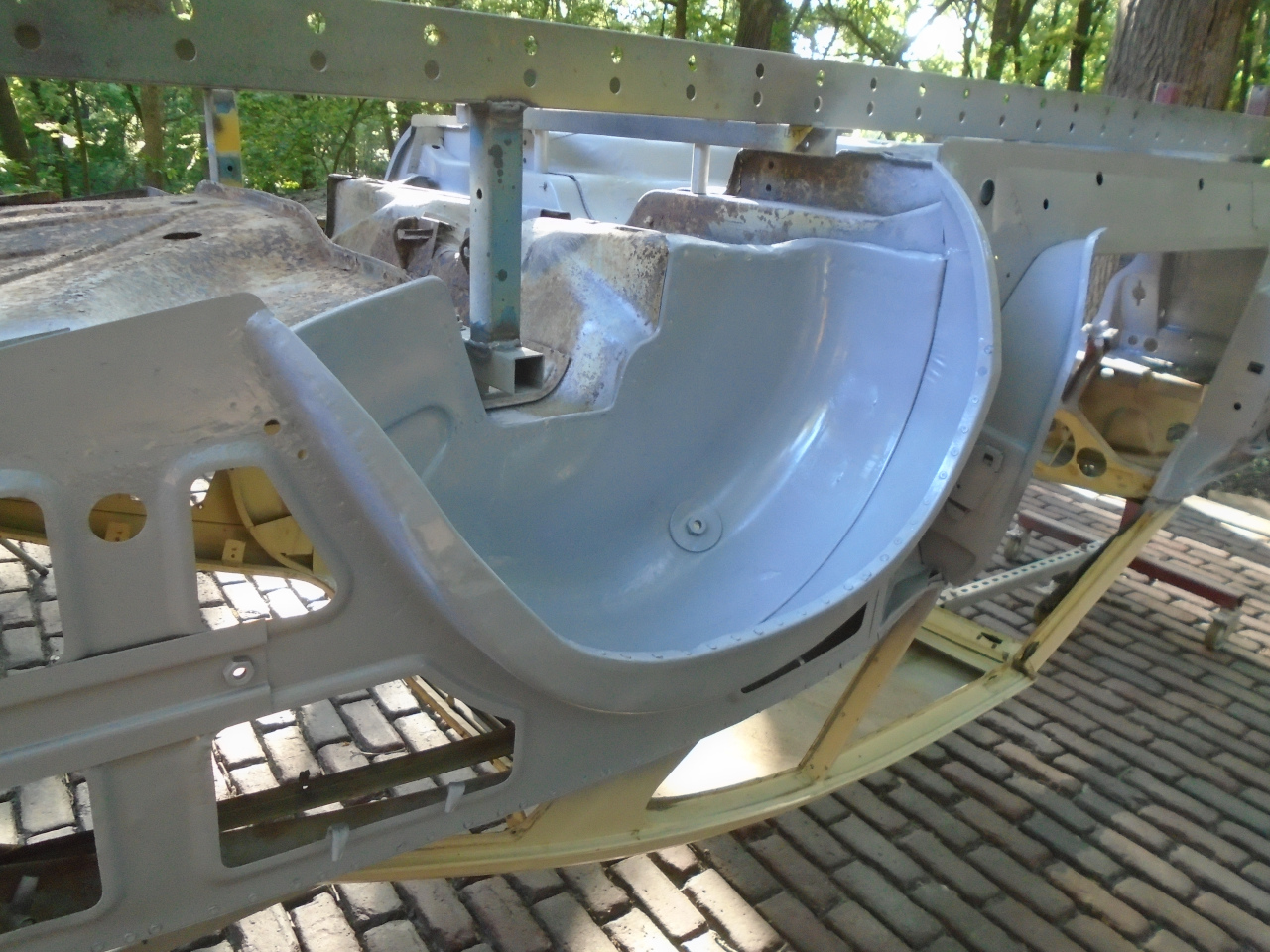

The top damper bracket was welded to a doubler plate that was in

turn welded to the wheel well sheet metal.

While that view may not look so bad, the fact is that water found

its way between the doubler and the wheel well, and went to work.

I managed to repair

the wheel well on both sides, but couldn't bring myself to

recreate that factory damper bracket.

I'm not the first one to feel this way, and there is even a

commercial solution available to move the top shock fixing back to

the frame, using an extension from the old MK1 mount point.

Though it's easy to order the kit to make the change, my Inner

Engineer rose up and parked himself between me and my keyboard.

"You don't need to order that", he said, "It's a good solid

Engineering problem to solve! Piece of Cake!"

"I don't know", I protested. "Seems like a lot of work."

"You really need to do more to keep your skills up, Dude", he

said, rolling his eyes. "Now close that window and open up some

CAD!"

So I did. I took some measurements from the suspension and

mocked up a simplified version of the mechanism.

The fixed line at the right represents the frame itself. The

upper horizontalish line is half of the transverse leaf

spring. The leftmost line is parallel to the plane of the

wheel, while the verticalish line just to it's right represents

the vertical link. The two diagonals that end in mid air

represent the tube shocks, the right one being attached to the

original MK1 chassis fixing point. The other one is the new

shock orientation, and the new adapter bracket's job is to span

between those two upper red dots.

The three red dots at the left represent, from bottom to top, the

point at which the axle hits the frame, the intended lower limit

of suspension travel, and the upper limit of suspension

travel. Since there are no explicit bump stops in this

design, the damper itself determines the distance between the two

limits.

The commercial design uses the original MK1 shocks, so I did,

too. In effect, the adapter just rotates the original MK1

shock outward just enough to clear the rotating axle parts.

Making the shock more vertical has other effects, though.

The travel of the MK1 shock itself is about 2 1/4 inches, but for

an angled shock, this translates to a little more travel at the

wheel. A more vertical shock reduces the travel.

So, I fiddled with the shock position and orientation for a while,

trying to balance the requirements: stay clear of rotating axle

parts, keep the axle from hitting the frame on rebound, and try to

keep suspension travel as close to stock as possible.

In my final design, the model predicts about 2 3/4" of travel at

the wheel. This is less than the MK1 travel, which I believe was

over three inches. It predicts about a minimum 1/4" gap

between axle and frame on rebound.

Now, I couldn't really take the predictions of this model as

gospel, mainly because it was so hard to get precise 2D

measurements from the actual 3D suspension. So the next step

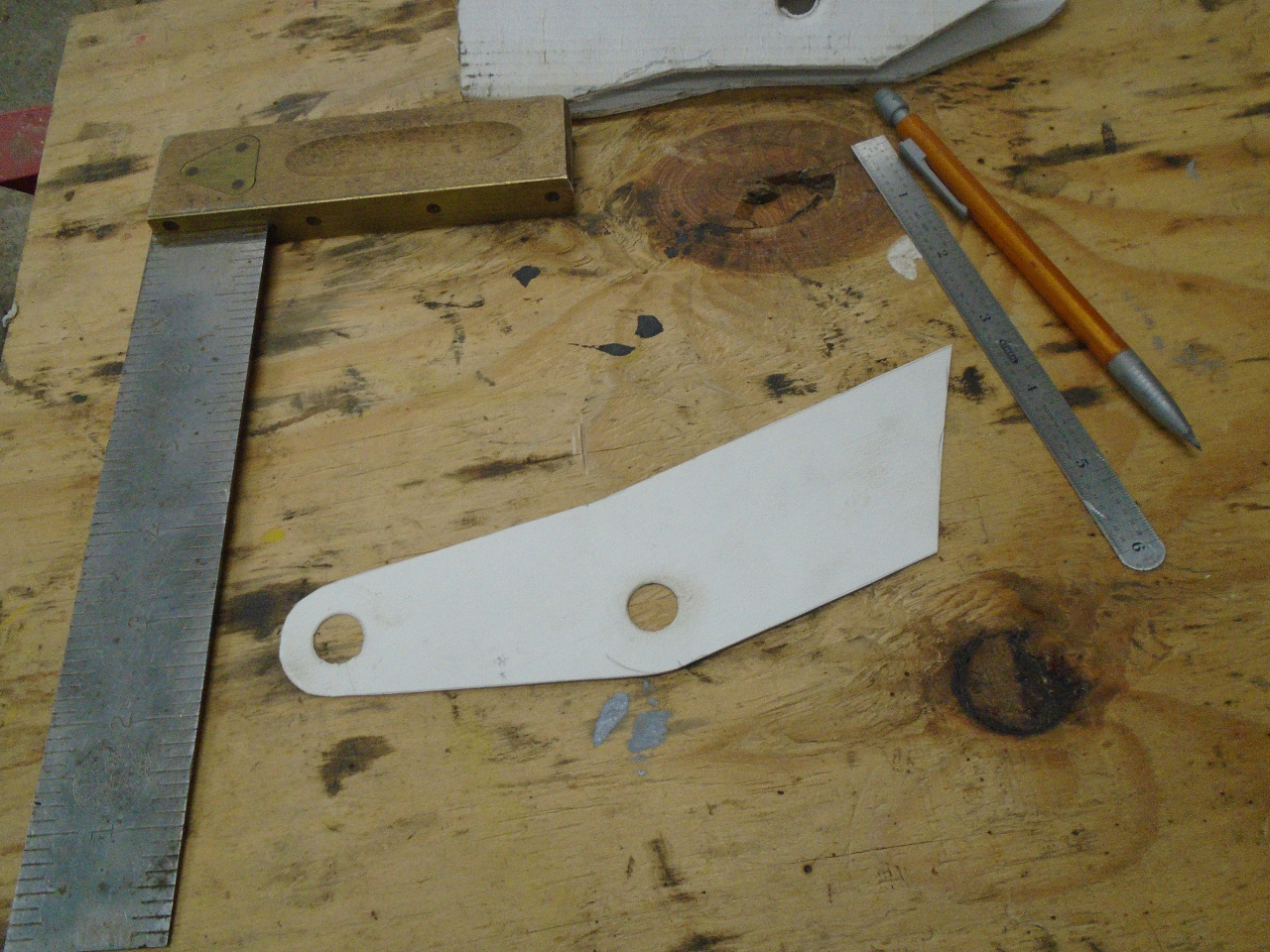

was to actually build the adapter. From computer model

measurements, I made a paper template to fit the existing bracket.

Then, cut some parts from 1/8" (11 gauge) steel. I was

feeling confident, so I cut parts for both sides.

The adapter would attach to the original bracket using the

original shock mounting hole, but it seemed like a good idea to

install a spacer inside so cranking down on the fastener wouldn't

just distort the bracket. Unfortunately, the hole on the

forward side of the frame bracket was larger than the other

one. This was probably because a large shoulder bolt was

used to fix the shock.

So, to get a spacer to work, I made these little stepped washers

to adapt the hole.

At this point, I could take some measurements to see if I still

agreed with the model. So far, so good. Next up was a

top piece to connect the two side pieces. This is

essentially the same design as the commercial adapter.

Before welding, I wanted to actually mount the shock. This

is a MK1 shock. It came with the rubber bushes, but not the

internal distance pieces. I had to make those.

Installed the shock, and everything still looked good, so welded

'er up.

Took it all apart, powder coated the adapter and plated the

hardware.

And put everything back together.

Hard to see in this bad pic, but with the suspension hanging from

the shock, the axle is about 1/8" from the frame rail. I

wish it were a little more.

I compared the dimensions of my final adapter with those that a

fellow enthusiast sent me that were reportedly taken from one of

the commercial adapters. They were very close. So, I

consider the design good enough. Right now, the chassis is

up on its top bunk and against the wall, so I can't do the other

side until I bring it down.

Even though my Inner Engineer sort of bullied me into this

exercise, I really do enjoy this kind of hands-on

engineering. I'm not sure what the commercial adapters cost,

but these were less than $10, just for steel and hardware.

Comments to Ed at elhollin1@yahoo.com

To my other GT6

pages