Source of the Missouri River

I've lived within a mile or two of the Missouri River just about my

entire life. I've camped on its banks, dinner-cruised it, rafted

it, and crossed over it thousands of times. I've seen it lazy and

slow, like a mud flow. I've seen it choked with jumbled ice

disks, piling up against bridge abutments. I've seen it angry and

flood-swollen well beyond its banks. I've seen it placid and

dangerous. It's been a fixture in my life, often out of sight,

but always near. It's like a friend, or maybe more like a

brother, where the bond has deeper roots.

I've been retired for five years now, and have really enjoyed not

traveling like I did when I was working. Staying home and

working in the shop or garage is pretty much what I've wanted to do

since I gave up gainful employment. Recently, though, I've

been feeling a little itch. I don't know exactly when or how

the idea started, but for at least a few years, I've had this notion

of a small adventure connected with the river. As the idea

evolved and matured, it took on the tone of an exploration more than

just a trip.

So, on Monday morning, I'm leaving on a road trip, generally

following the Missouri upstream to its ultimate source.

The true "Ultimate Source" of the Missouri is not a secret, though it

wasn't discovered until nearly a century after Lewis and Clark explored

the Missouri. Lewis and Clark's original declaration of the

Missouri source was incorrect. The true source is apparently an

isolated spring high in the Centennial mountains of southern

Montana. The spring is named for explorer Jacob Brower, who

discovered it, but neither the location nor the name shows up on

any USGS or State maps I could find. Though people have been

there and written about it, it apparently isn't accessible by car, and

is reportedly not marked with any sort of signage.

Sunday, August 12, 2018

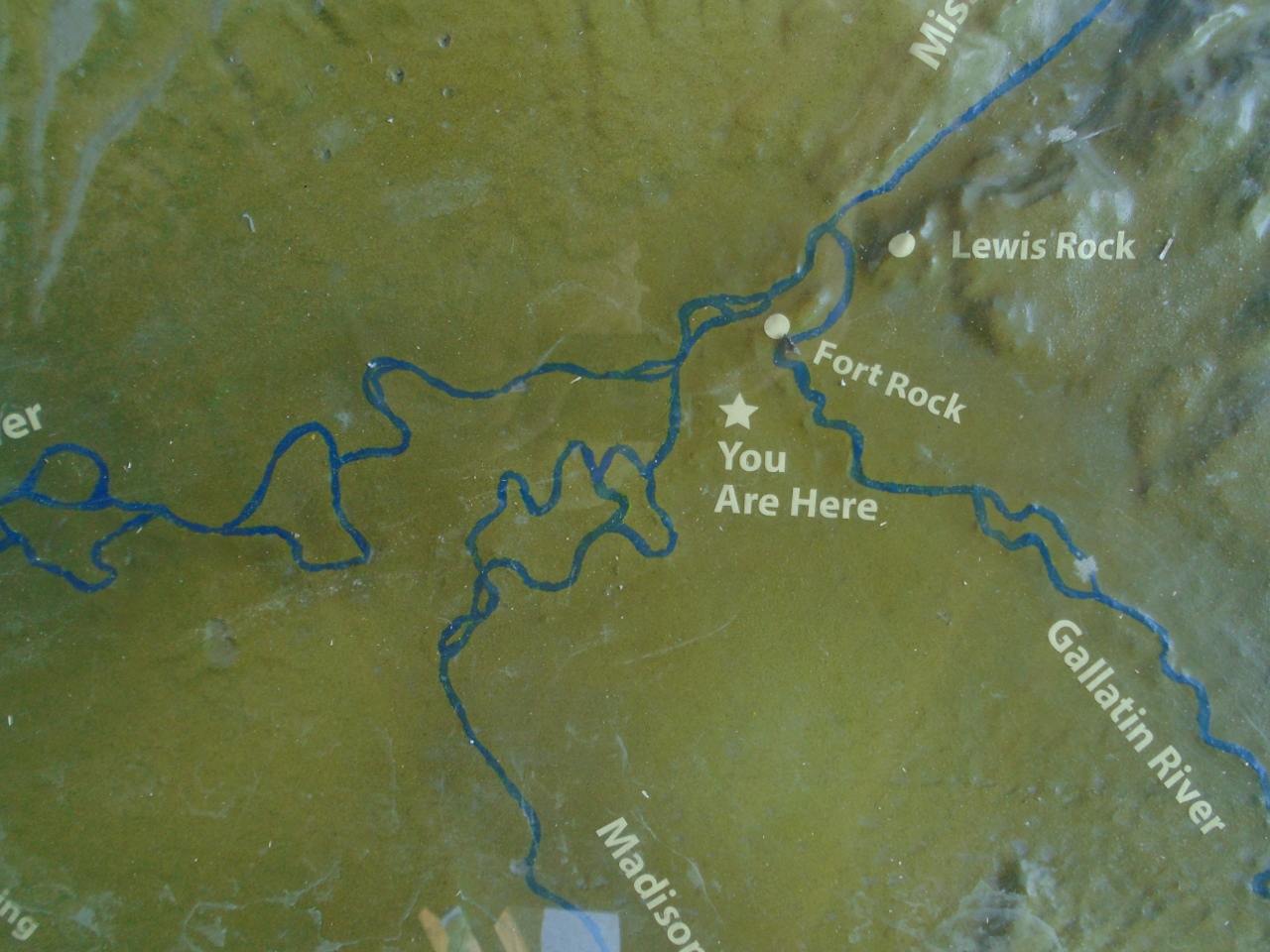

The Missouri is the longest river in North

America. Though some geography books teach that the Missouri

starts at Three Forks, Montana, this is not really correct.

When Lewis and Clark explored up the Missouri, they had the

authority and responsibility to name many of the tributaries joining

the river. In many cases, they would use the name the local

inhabitants used, or some variant of it. But they followed the

convention that the main river's name would continue with the

longest branch. At Three Forks, however, they rejected

convention, and gave each of the three joining streams a new

name--the Jefferson, the Madison, and the Gallatin, after the then

current US President, and the Secretaries of State and Treasury,

respectively. Now, maybe this was because they simply didn't

know which of the three streams was the longest, and maybe it was

just brown-nosing their bosses.

A similar thing can be said about the confluence of the Missouri

with the Mississippi. Had the naming followed convention, the

Missouri name would continue to the Gulf of Mexico. For this

reason, the Missouri River System, extending as a single continuous

stream from the Rocky Mountain spring to the Mississippi Delta, is

the fourth longest river in the world, behind the Amazon, the Nile,

and the Yangtze.

Below, from left to right--The Bob Kerrey Pedestrian Bridge, near downtown

Omaha; view from the bridge looking north; the Mormon

bridge north of Omaha, near the site of a ferry that the Mormons

used in their migration of 1846. Pics are clickable.

Monday, August 13

Any river can cause damage when it floods, but one the

size of the Missouri can cause catastrophic mayhem. The

average elevation change of the river through the Great Plains is only

about a foot per mile, so it tends to be slow and to meander a

lot. This creates a very wide flood plain and braided, shifting

channels. For this reason, the US Army Corps of Engineers was

assigned the task of minimizing flooding. They do this by

damming the river to allow more consistent flows, and channelizing

it so that it has more defined and stable banks. The state of

South Dakota alone has four major dams on the Missouri. From

south to north: Gavins Point Dam, Fort Randall Dam, Big Bend Dam,

and the massive Oahe Dam.

To preserve some notion of how the river looked historically, the

Corps has set aside two stretches of the river in South Dakota, each

of a few dozen miles, with no damming, and no channelization, and no

other tinkering. It is strikingly obvious when looking at a

map of the river how different it looks in these areas. The

river is wider, with many islands and braided channels.

This is a picture of Mulberry Bend in one of the hands-off areas

near Yankton, SD.

This is the spillway of the Fort Randall Dam. The dam backed

up the river for over 100 miles, forming Lake Francis Case.

A view of the river from a bluff near Chamberlain, SD

Tuesday, August 14

The river is getting noticeably smaller as I go upstream, and the

flood plain is narrower. The river cuts through more limestone

up here, rather than the softer, loess type deposits farther south.

Here is what the river looks like just out of Bismarck, ND:

And another 50 miles upstream at Washburn.

The largest dam on the Missouri, at least in terms of storage is the

Garrison dam in North Dakota. Lake Sakakawea behind the dam

stores nearly 24 million acre-feet of water (almost seven cubic

miles). I paralleled the lake today for nearly 180 miles.

For such a large lake, its output stream is pretty modest.

Wednesday, August 15

Going upstream after leaving Nebraska, the Missouri cuts South Dakota

in half vertically, thrusts into the belly of North Dakota past

Bismarck, then starts a wide arc to the West into Montana. It

comes within about 90 miles of the Canadian border before falling south

through Great Falls and Helena. This is of course backwards from

the way the river's water actually flows, but as upstream explorers,

it's probably the way Lewis and Clark thought of it, though they

obviously wouldn't have known about the modern place names.

Coming into Montana, the river has cut canyons in many places.

This is near Culbertson just across the border. The river is

noticeably smaller. The good-sized Yellowstone river joins the

Missouri just a few miles downstream from here

Other places are flatter with wide flood plains. This is near

Wolf Point, MT. The Wolf Point Bridge is an abandoned 1930s

structure that is maintained as a classic example of its design.

Near Fort Benton, MT, the river has cut a very wide canyon.

Between Wolf Point and Fort Benton, the Fort Peck dam stores the

Missouri's water in the 130-mile long Fort Peck Lake. It is

pretty remote, and most of the lake shore is difficult to access by

road. Skirting around the lake took me within about 40 miles

of Canada.

This is the river near Craig, MT, between Great Falls and

Helena. It's looking a little more like a mountain stream now.

Thursday, August 16

It isn't easy to imagine how isolated these areas were when they

were first explored. What I've traced in a few days took Lewis

and Clark over a year to discover. The inspiring thing is that

there are some places that surely look essentially the same today as

they did then.

This is the Missouri a little downstream from present day Townsend,

Montana.

Ask 100 people where the source of the Missouri River is, and the

second most common answer will probably be "Three Forks,

Montana". (The most common answer would likely be "I

don't know"). I think it's what I was taught in school.

Though it isn't the source of the river, it is historically notable,

and it is the place where the name Missouri is retired. Three

rivers--the Jefferson, the Madison, and the Gallatin come together

here to form the Missouri. The actual confluence is sort of

spread out in a broad valley, so it's a little hard to sort out from

ground level. The third picture below is the combined

Jefferson and Madison before the Gallatin joins them.

We know today that the ultimate source of the Missouri is up the

Jefferson River. The first pic below is the Jefferson about 50

miles upstream from Three Forks. The river is popular with

floaters. I found the sign sort of funny.

The Jefferson River has its own Three Forks near where the above

picture was taken. The Beaverhead River, the Big Hole River,

and the Ruby River join to form the Jefferson. The Beaverhead

leads to the source. This is the Beaverhead as it pass through

the town of Twin Bridges, Montana.

The Beaverhead runs for about 50 miles. It is fed from the

Clark Canyon Reservoir. The largest stream feeding the

reservoir is the Red Rock River, which is shown below about another

50 miles upstream.

This is about as far as I'm able to go upstream with the gear that I

have with me. The roads have gotten pretty bad, and it's about as far as they go anyway. The Red Rock

picture above took a bit of a hike off the road. I do know that the

Red Rock River is fed by the coolly named Hell Roaring Creek, and

the creek is fed directly from the source spring. I knew all

along that I wouldn't be able to get to the spring this way, so my

plan is to access the spring from the other direction. This

will take about a hundred mile detour around the essentially roadless

wilderness that holds the spring.

Friday, August 17

I was only able to get within about 30 miles (as the crow flies) of

the spring by the upstream route. It would have been a several

day pack trip that I didn't sign up for. This was anticipated

though, so I had a Phase II plan to access the spring from the

east. The closest road east of the spring is the Sawtell Peak

road. It is a narrow, scary, 15-mile gravel road that serves a

weather radar installation on the mountain peak.

The Sawtell road is in Idaho, and Hell Roaring Creek Canyon is in

Montana. The Montana-Idaho border in this area is the also

Continental Divide, and this is a place where the Divide curls back

on itself, so that locally, Idaho is east of Montana, and the east

side of the Divide drains to the Pacific Ocean, while the west side

drains to the Missouri and the Gulf.

The area is fairly rugged, but doable without any special mountain

equipment.

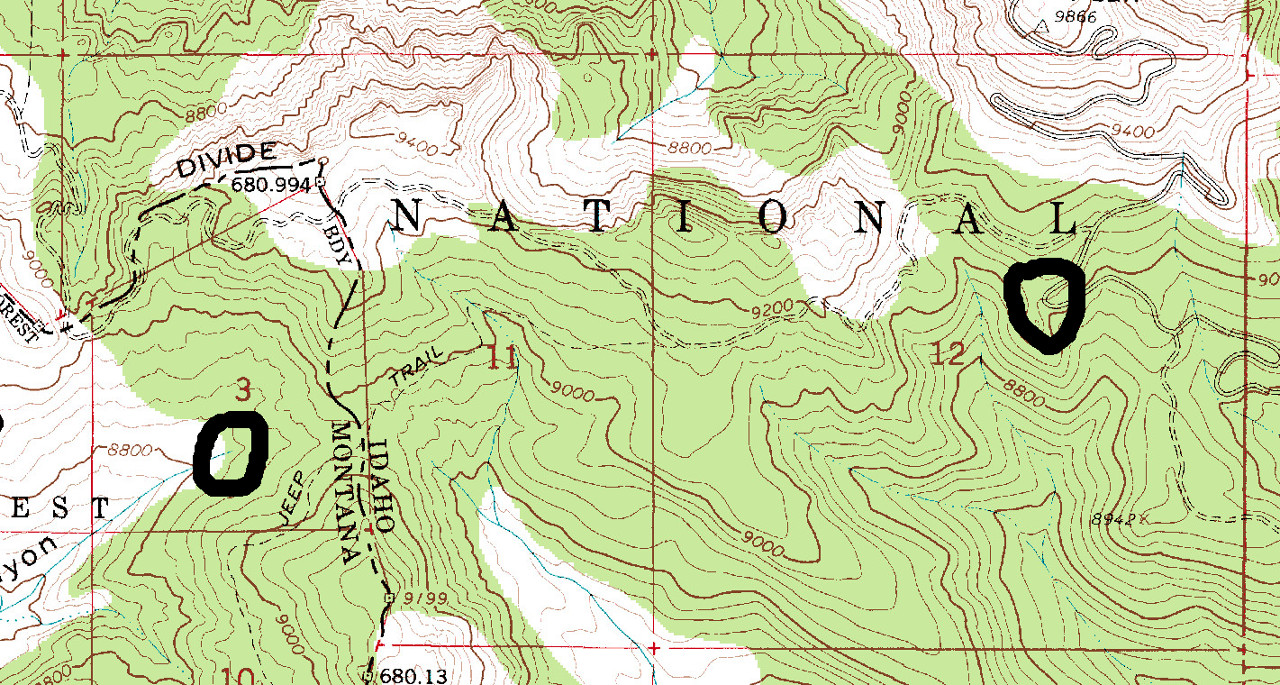

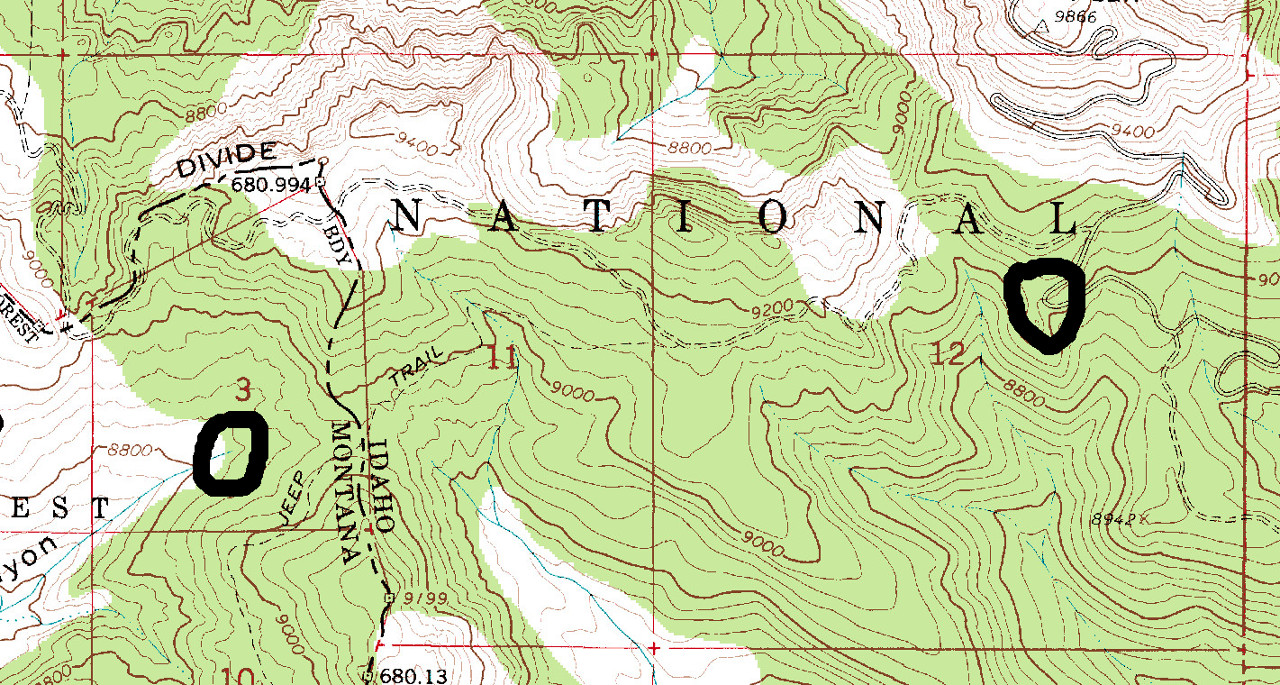

The USGS map shows what appears to be a road coming off the Sawtell

Peak Road, and I had planned to just drive that road if

possible. I'm driving a four wheel drive truck, but it isn't

really designed for serious off-road use. Well, that "road" is

no more than a narrow hiking trail. No way a normal sized vehicle could

negotiate it. The map also shows a "Jeep Trail".

This is a laugh, too. So, it was all on foot from the Sawtell

Road. The trailhead was marked, but made no mention of the

spring.

I didn't have any trouble following the main trail, but the "Jeep

Trail" was pretty faint in places. The terrain was up and down

a lot, with scattered trees and some open areas.

According to the GPS gizmo I had with me, this was the Continental

Divide. Rain falling on the left (West) side of the picture would go

to Hell Roaring Creek and to the Missouri.

The spring is not on the trail, so I had to use GPS to help me

navigate off the trail. I got to the area where the spring

should be, and I didn't see anything. I wandered around some,

going up a few dry washes without finding anything. After

about an hour of this, I was ready to give up and assume the spring

was dry. As a last resort, I decided to go a little further

down the canyon from the GPS location. Then I saw it.

I had completely forgotten about the cairn marking the spring, but I

had seen it in pictures, so I recognized it immediately. The

actual spring is about 20 yards behind the cairn, and nestled down

in the rocks, so it isn't visible from this location.

Scrambling down the rocks, I saw a little grotto with a tiny pool at

the base.

This is a little down stream, looking back up at the spring.

So this is Hell Roaring Creek, Mother of the Mighty Missouri.

After sitting a while at the spring, it was time to go. It was

still early, but if I got lost going back, I wanted plenty of time

to get found.

I stopped by the cairn to look for the message box. It was

right on top. It contained missives from previous

visitors. I added mine and replaced the box.

Almost forgot the proof shot.

After about three hours of hiking time and another hour up and down

the mountain, I was hot, tired, and hungry. This was just a

little serendipity I saw as I came to the main highway. Ain't

civilization great?

I only saw a few other hikers on the main trail, apparently locals. I

asked them if they were going to Brower's Spring, but none of them

seemed to know anything about it. I saw no one on the trail

that went toward the spring, and, other than the message box and the

faint trail, not much evidence that anyone had been there. This

is a little puzzling to me. On the other hand, I think it's

good to maintain a few secret places here and there. I just

hope that in 20 years, there isn't a gift shop at Brower's Spring.