To my other GT6

pages.

April 18, 2020

Horns

My car, and most Triumphs of this era

came with a pair of Lucas 9H Windtone horns. These were

pretty widely used at the time, even seeing some duty on

motorcycles. The horns look similar, but are different in

that one honks a higher note than the other.

Considering where the horns live, right inside the front grille,

they didn't look too bad--just dirty and rusty. You can

just make out the "H" and "L" markings on the mouths of the

horns, indicating the high and low note units, respectively.

I tested the horns to a 12 volt power supply, and they both were

trying, but the tones were weak and erratic. I measured

the resistance across the terminals. It should be

something less than one ohm. The fact that the resistances

weren't infinite was a good sign, but he high readings probably

indicated dirty contacts inside.

I do know that generic horns for cars are a commodity item--they

can be bought cheaply at any auto store. There are even

reproduction Windtone horns available for not much money.

Either of these options would be thoroughly sensible.

But that's not the way I roll.

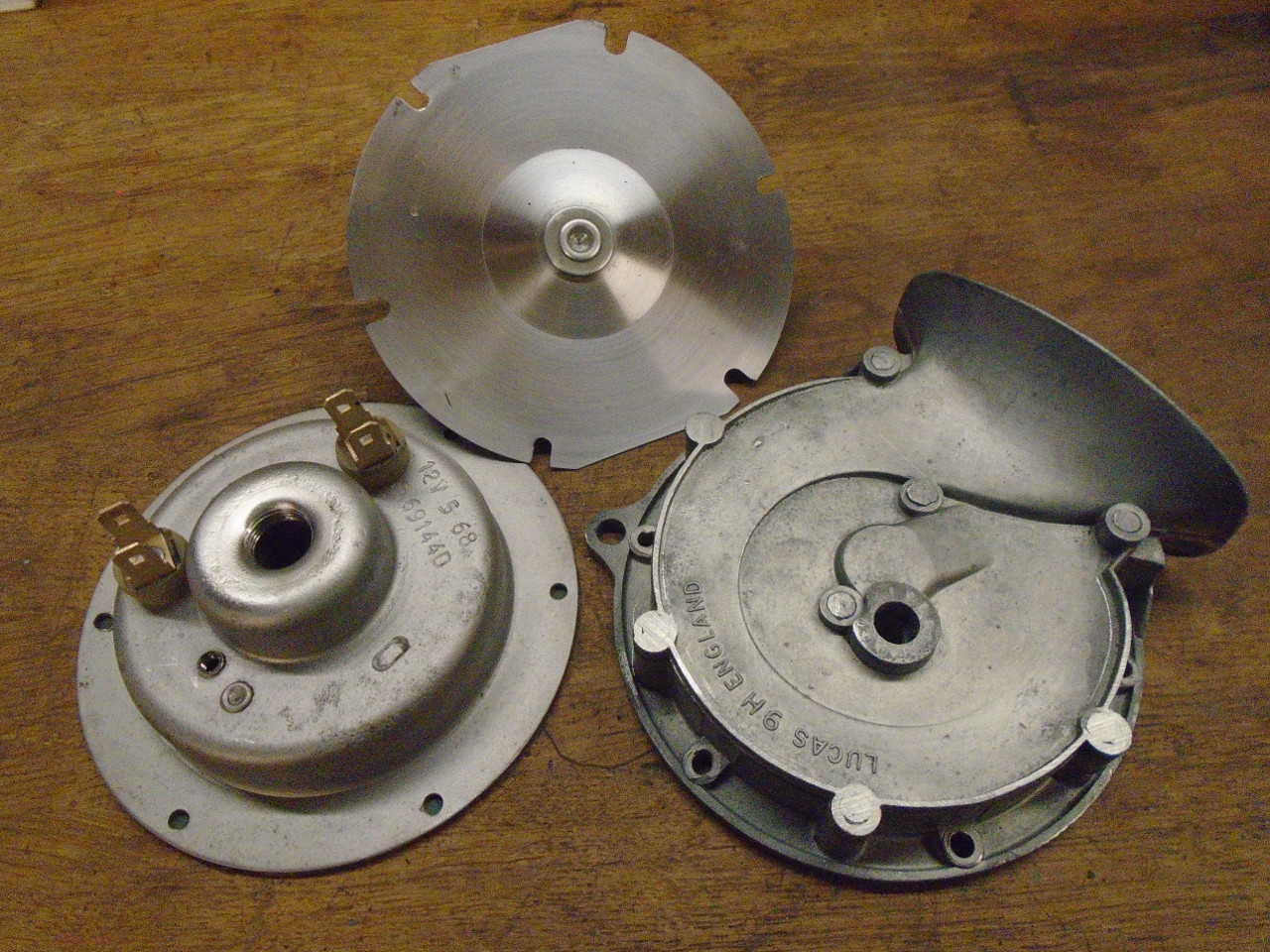

So I had to break into the horns. They are each held

together with six rivets. Drilling those out revealed that

the horn was composed of two body halves with a thin metal

diaphragm sandwiched between. One body half was a pot

metal casting of a rolled up horn shape.The other half contained

the electrics: a coil of wire forming an electromagnet, and a

set of contacts in series with the coil. With the contacts

normally closed, 12 volts applied to the external connections

will energize the magnet. It pulls in a steel slug

attached to the center of the diaphragm. After traveling

some small distance, a collar on the slug contacts a finger on

the contacts, opening them. This stops the current, and

the slug retreats to start the cycle again. This of course

happens hundreds of times per second. The vibrating

diaphragm gets air moving, and the horn shape of the channel

leading to the outside reinforces the sound.

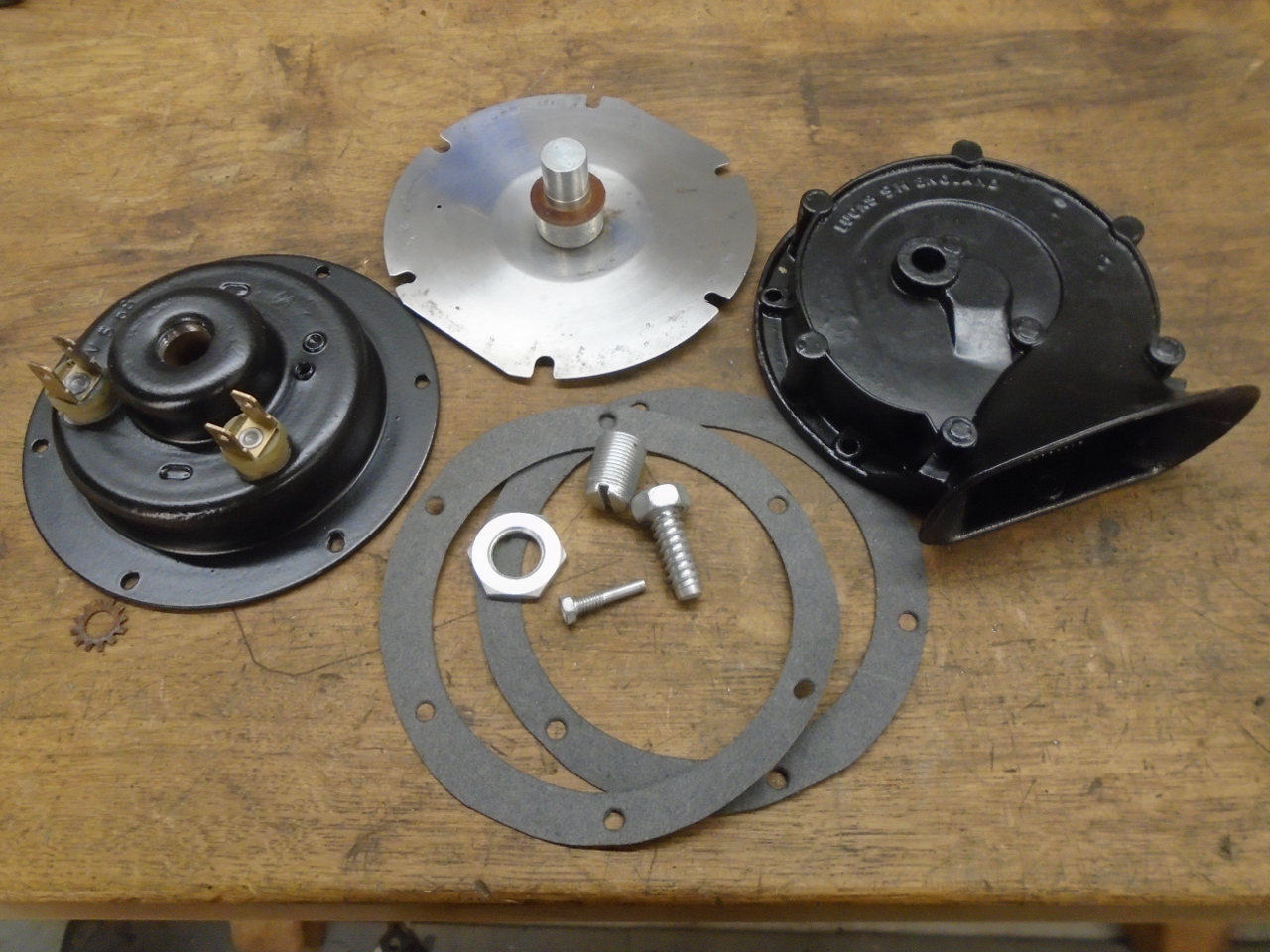

Everything cleaned up pretty well with a light blasting. I

powder coated the horn casting, but was a little apprehensive

about subjecting the electrics to the oven heat, so that half

was just primed and painted. Not much hope of finding

those gaskets, so they are home made.

Cleaned the contacts by pulling a strip of very fine abrasive

paper through them, and put everything back together. I

did one unit at a time in case I had to refer to the virgin

unit.

The second one went a lot faster. There are two

adjustments on each of these horns. First, there is a big

threaded stud and lock nut. The stud is a stop for

the diaphragm stud, limiting how far it can travel.

Second, there is a small screw that bears on the fixed side of

the contacts, allowing it to be moved slightly. Oddly,

that screw is left hand threaded.

I measured the protrusion of both of the adjustment screws

before I removed them, so I could at least have a good starting

point for tweaking them. Neither of the screws changed the

pitch of the horn--they are just mechanical adjustment of the

circuit-breaking action of the contacts. If they are too

far from optimum, the horn just clicks or grunts.

One horn worked fine after assembly without much tweaking.

The other wouldn't do anything. After fiddling a lot with

the adjustments, I finally measured the resistance. It was

around 12 ohms, suggesting some crud still in the

contacts. So, apart it came for another contact cleaning,

and that did the trick.

Factory frequency spec for the horns is 390-400Hz for the low

tone horn, and 490-500 Hz for the high one. My horns were

in or very near spec, together approximating most of a

harmonious G major chord.

I like quick and fairly easy projects like this. Low

stress, good chance of success, and little or no

investment. And it was good for a few pleasant afternoons

in the shop. Cost was essentially zero.

Comments to Ed at elhollin1@yahoo.com

To my other GT6

pages.